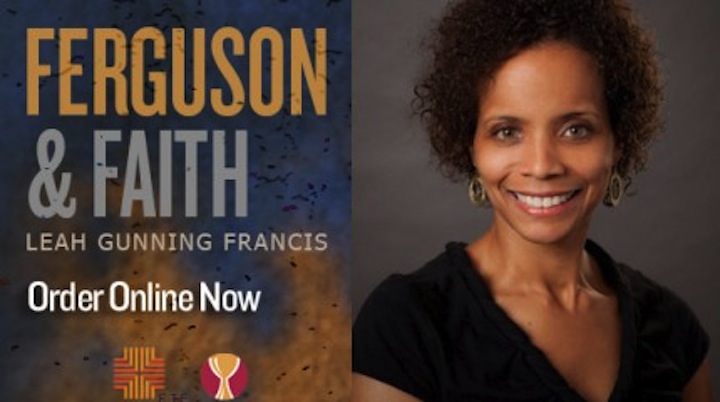

August 9th marks the one-year anniversary of the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. With the rally cry “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot, ” emerging young leaders of today’s Civil Rights Movement in the St. Louis area led a nationwide movement to challenge systemic racism and the over-policing of their community. Seminary professor Leah Gunning Francis has lived and moved among these young activists. Interviews with more than two dozen faith leaders and with the movement’s new organizers take us behind the scenes of the continuing protests in her new book, , which Chalice Press will release this week. Red Letter Christians interviewed Gunning Francis about the book and what it offers followers of Jesus in America today.

You’ve written a book on Ferguson and Faith. A year ago, I didn’t know where Ferguson was. What is required for people of faith to know America’s Fergusons?

Fergusons are all around us, and there is a Ferguson near you. In order for us to see “Ferguson” in our own community, we have to be willing to listen to the stories of those who face discrimination and marginalization. In the book, Unitarian Universalist minister Krista Taves, who serves a congregation in a majority white, affluent suburban community, tells the story of a young congregant from Cambodia who shared a testimonial with the congregation about the discrimination and isolation she deals with on a regular basis. Her testimony was called “The County Brownie, Death by 1, 000 Cuts.” She talked about the humiliations she endures, such as having to leave her purse at the counter in the local pharmacy every time she enters. Her adoptive white mother gave a testimony titled “White Soccer Mom” and expressed her anger at not being able to protect her daughter from these and other discriminative acts. By the end of their stories, many were in tears and shocked to learn this family endured such pain. But they did not stop there. The pastor asked the congregation how they felt called to respond. They decided to wage an awareness campaign about racial discrimination in their own backyard.

As I talk with folks in churches–especially white churches–these stories of discrimination and overt racism are met with disgust. Most Christians don’t want to be associated with racism. But the same people struggle to see how a police officer questioning, searching or arresting a suspect is racism. How does Ferguson help us understand the systemic nature of racism?

The Department of Justice’s Ferguson report revealed the way in which the town’s budget us heavily subsidized with traffic fines. The number of police stops disproportionately affected black people. This report alone helped us to see the way racial discrimination is perpetuated in a systemic way.

The data doesn’t lie. You’re right, if we’re willing to pay attention, the disparities are there–if not in intent, at least in effect. But these disparities aren’t new. What has kept us from paying attention? And if love of neighbor is at the heart of faith, why are church folk often worse than average at paying attention to systemic racism?

Sometimes it’s difficult to pay attention to something that doesn’t affect you personally. That’s what privilege does. It allows you to choose what you pay attention to. Ferguson forced many to see a reality they chose not to believe- the reality that black lives have not mattered in the same way as white lives. Now Christians are called to decide: will you stand on the side of love or privilege? Through this movement for racial justice, many have chose to wage a kind of love that demands nothing less than seeing black people as children of God, created in God’s image, and deserving of being treated as full human beings.

For Christians who aren’t living in Ferguson, MO, what does it look like to wage love in their communities? What do you say to white folks who want to do something but don’t know any black Christians in their own hometown?

Millennial activist Brittany Ferrell says in the book “I think clergy involvement has showed me that the church does not always have to exist within those four walls. I feel like there’s this perpetuated idea that “church” is something you go to, and it’s been proven wrong within the last six months, because church has come to us whether we welcomed it or not. It was there. We became the church.” To wage love is to do justice, and to do justice requires us to move beyond ourselves and out into the world in tangible ways. When we wage love, we ask questions before we make assumptions in order to seek understanding. For white people who don’t know any black Christians, the first question to ask is “why?” Is it because of red lining that has kept black people from easily moving into predominately white neighborhoods? Or is because you’ve never asked “would black people feel welcome in our church?” Do you not know black Christians because few black people have been hired at your workplace? Or is it because you’ve never sought to form a relationship with those who are there? To wage love is to look around and ask the kind of probing questions about racial justice that can lead to corrective action.