‘I may never march in the infantry, ride in the cavalry, shoot the artillery. I may never fly o’er the enemy, But I’m in the Lord’s army! Yes Sir!’

This song was one of my first exposures to the Christian faith. I remember singing it proudly, with my hand over my heart and head held high in my Baptist pre-school. I wasn’t sure what most of those words meant, but I remember thinking that it was really cool that I was in God’s army. I didn’t remember ever formally enlisting, but hey, my teachers told me I was in, and I was more than happy to be a soldier. What other five-year-old could say that?

From the earliest days of my life, I’ve understood the Christian faith in militaristic terms. When I became a follower of Jesus at the age of twelve, I drew heavily on these early memories of Christianity and began to frame my new life in Christ as enlisting in a spiritual militia of sorts. My pastor spoke of spiritual warfare against the forces of darkness that were prevailing in our culture. The Christian televangelists I watched incessantly talked about how Christians were being persecuted and how we would need to pick up our swords (which supposedly meant Bibles) and go to war against the forces that sought to destroy Christ’s Kingdom.

I began to understand that the militaristic language I had learned in preschool wasn’t just cute imagery that they put in kids’ songs. It was serious. I was really supposed to believe that I was in a literal battle against the forces of darkness. This new reality that I lived in was always abuzz with talk of the latest ‘threats’ to the body of Christ, calls to go to battle against the ever-growing list of enemies of the Kingdom, and talk of ‘taking back ground’ that had been stolen by ‘the devil’ which usually meant ‘liberal politicians’.

I understood that for the time being, my duty as a Christian in the battle was to stand boldly against the enemies of truth that surrounded me in my everyday life. For me, this looked like burning my blink-182 CDs and wearing pro-life buttons on my backpack. But I was also taught to believe that one day, when Jesus returned, I’d actually get the chance to engage in real, flesh and blood warfare. On that day, I’d be given a horse and a sword and we would all ride into Jerusalem poised to destroy, once and for all, the Anti-Christ and all who sided with him (which was everyone who was not a Christian). These thoughts always made me pretty uncomfortable, but at the same time, I believed that this final, bloody battle needed to take place for peace to be established on earth as it is in heaven.

This mindset of warfare continues to be predominant in some versions of “Christianity.” This eschatology (or theology of the end times) is taught to thousands in megachurches and millions by televangelists every single week. And even though the average Christian isn’t actually militaristic, this mindset of war does affect the way we interact with the people and culture that surround us. We begin to see everything in our world as increasingly dark and hostile to us and our faith. We begin to view every news story through the lens of our eschatology, believing that every political decision that doesn’t align with our worldview and every artefact of pop culture that doesn’t expressly promote our values as a sign of the end times and as an attack on our faith.

It’s this impulse to defend our faith against perceived threats that has made Christians more known for what we’re against than what we’re for. In 2007 a Barna poll revealed that just 3 per cent of all young people from the ages of 16-29 had a favourable view of Evangelical Christianity and 91 per cent said that the most common perception of Christianity was ‘anti-homosexual’, followed by 87 per cent who said Christians were ‘judgemental’. When this poll came out in conjunction with Dave Kinnaman’s book UnChristian, the Evangelical world was reeling. Churches and denominations came together to seek to find ways to change the culture’s perception of the Christian faith. But nearly a decade later, I think it’s safe to say that the perception hasn’t changed at all, in large part, because it seems that the primary impulse of modern day Christianity is the impulse to defend and go to battle against our culture. When the culture strikes back at the Church, say, by trying to pass legislation that would take away churches’ tax-exempt status, we cry persecution, which only further ingrains the war mindset into the consciousness of Christians.

During the summer of my freshman year in college, I went on a choir tour to Greece and Cyprus. One of the memories that is seared deep onto my mind was during our tour of Athens. After climbing up the long, rugged staircase that leads to the Acropolis that stands mightily above the city of Athens, we stopped and looked out over the ancient city. The view was breathtaking. As we began to wander around the ancient temple, our tour guide noted that for a number of centuries the Pagan temple to the goddess Athena had actually been converted to a Christian church. Of course, this piqued the interest of a group of Bible college students.

Our guide went on to explain that during Christian ‘evangelistic’ efforts, a mighty Christian army came speeding towards Athens with the mission of killing everyone in the city who did not profess faith in Christ. The quick-witted people of Athens immediately devised a plan to save themselves and their metropolis, filled with magnificent temples and shrines to their pagan demigods. When the crusaders approached, the Athenians flocked to the banks of the sea and were ‘baptised’ Christian. Following this magnificent conversion, they made their way back up to the temple of Athena with the crusaders. Yet instead of calling it a temple of Athena, they claimed it was a sanctuary to Mary, the holy mother of God. As you can imagine, this greatly pleased the Christians who believed that Mary was the protector of them on their mission to Christianise the world by force. So these ‘evangelisers’ moved on, leaving very little damage or bloodshed in their wake. Of course, after the Christians were long gone, the new converts abruptly reverted to their pagan practices. The cunning minds of the Athenians had out-smarted the Christians and saved their lives, their culture, and their religion.

How much of our culture in the West is just like this? How many politicians and celebrities feel compelled to embrace the label ‘Christian’ in order to appease the powerful Evangelical population? Over the short history of the United States, Christians have continued the legacy of the crusaders, believing we have a divine mandate to ‘win our nation for Christ’, which, ironically doesn’t mean living as lights in our communities, loving our neighbours, doing justice, or even sharing the Gospel. Instead, it usually means winning positions of cultural and political power and authority and imposing our worldview and values on a nation in which our perspective is increasingly becoming minority. We feel compelled to fight for prayer in our public schools and for Creationism to be taught in the classroom, but what part of the great commission does that fit into? We vocally war against legislation to support same-sex couples’ civil right to be married under the law, claiming that marriage is ‘our’ institution. But when did Jesus, or Paul, or Peter, or anyone ever ask us to do that? As we force our worldview and values on a nation that cannot relate to them, is it any wonder that there are such negative perceptions of Christianity?

Because if that’s Christianity, even I want nothing to do with it.

Thankfully, that’s not the faith modeled by Jesus. That’s not the way of the Kingdom. The truth is that the Good News of the Gospel is not actually synonymous with Fox News … or MSNBC for that matter. It’s better than that. It transcends political, social, ethnic, sexual, religious, economic, and gender divisions and brings us all together as one new humanity in Christ. The whole concept of warring against our culture or against non-Christians is an idea that is completely foreign to the Scriptures because the Christian way isn’t one of shoving our ideas and values down the throats of our neighbours, but is instead, finding creative ways to live as followers of Christ within every culture. If the example of the early church tells us anything, it is that the way of Jesus can and must be adapted to and moulded to fit within different cultural contexts. Christians are called to be creative, discovering innovative ways of expressing our faith in ways that are consistent with our cultural context.

For example, in Acts 17, the Apostle Paul is preaching to crowds of Greek scholars and philosophers. When he describes the Gospel to these well-educated, cosmopolitan men, he references an eclectic mix of Greek poetry, religious tradition, and philosophy to communicate what it is that Christianity is all about. In the centuries following, as Christianity spread throughout the world, missionaries adapted the message and practices of the Christian faith to reflect the predominant cultural norms in each society. In many pagan cultures, the Sun god became the ‘Son of God’, using the same images and icons that the pagans had been familiar with but adapting the narrative of the Sun god to reflect the Gospel account of Jesus. This wasn’t a way of watering down the message of the faith nor was it a sly tactic in order to trick converts. Rather, it was understood that because of the universality of the Gospel message, it could and should be incarnated into each culture, representing God’s unique word of salvation to every nation, tribe, tongue, and group of people.

The modern pursuit of winning over the culture is ultimately a pursuit of power and domination. In the Western World, Christians have enjoyed a position of privilege for centuries. We have been at the forefront of the creation of culture and have often been the ones who have held the highest positions of power in the world. And while many great contributions have been made by Christianity because of its position of influence over the centuries, the truth seems to be that whenever Christianity is given power and prominence, it ceases to be authentic Christianity. Whenever Christians become obsessed with the pursuit of political power they fundamentally fall out of step with the way of Jesus. Jesus demonstrated this time and time again in his life. The least are the greatest in the Kingdom of God and the first will be the last. Those with the least privilege and power, according to Jesus, are the ones with the most potential to change the world.

History has even proven this. Major transformation has never come from the White House or Westminster. Instead, those who have changed our world for the better are those who had little power, prestige, or privilege. Mother Teresa, Martin Luther King Jr., Mahatma Gandhi to name a few of the more popular examples. But there are countless others who live their lives according to the subversive rhythms of the Kingdom of God each and every day and who are are bringing substantial transformation to their communities, cultures, and world. We may never know their names. Their communities may marginalise them. They may never have much material wealth in this life. But the truth is that God is pleased to make his appeal and to work through these men and women – the least of these.

For the past few months I’ve been living in Washington, DC. Though I haven’t been engaging in the political sphere very long, I have already become utterly convinced that if the hope of our nation and world lies in politics and lawmakers, then we are most certainly doomed. Policies and laws can have substantial effects on the lives of a nation’s citizens, but if we are looking for true, substantial transformation, it can only come by way of men and women who live humbly and subversively as incarnations of Christ in their culture.

Not through culture wars. Not through legislation. Only through love.

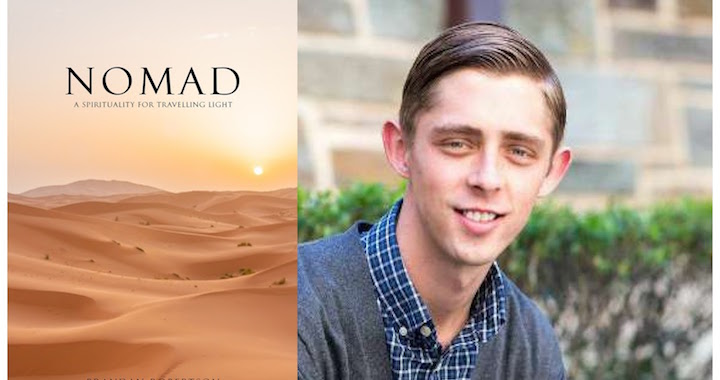

Excerpted from Brandan Robertson’s new book Nomad: A Spirituality for Traveling Light (DLT). Learn more at www.brandanrobertson.com.