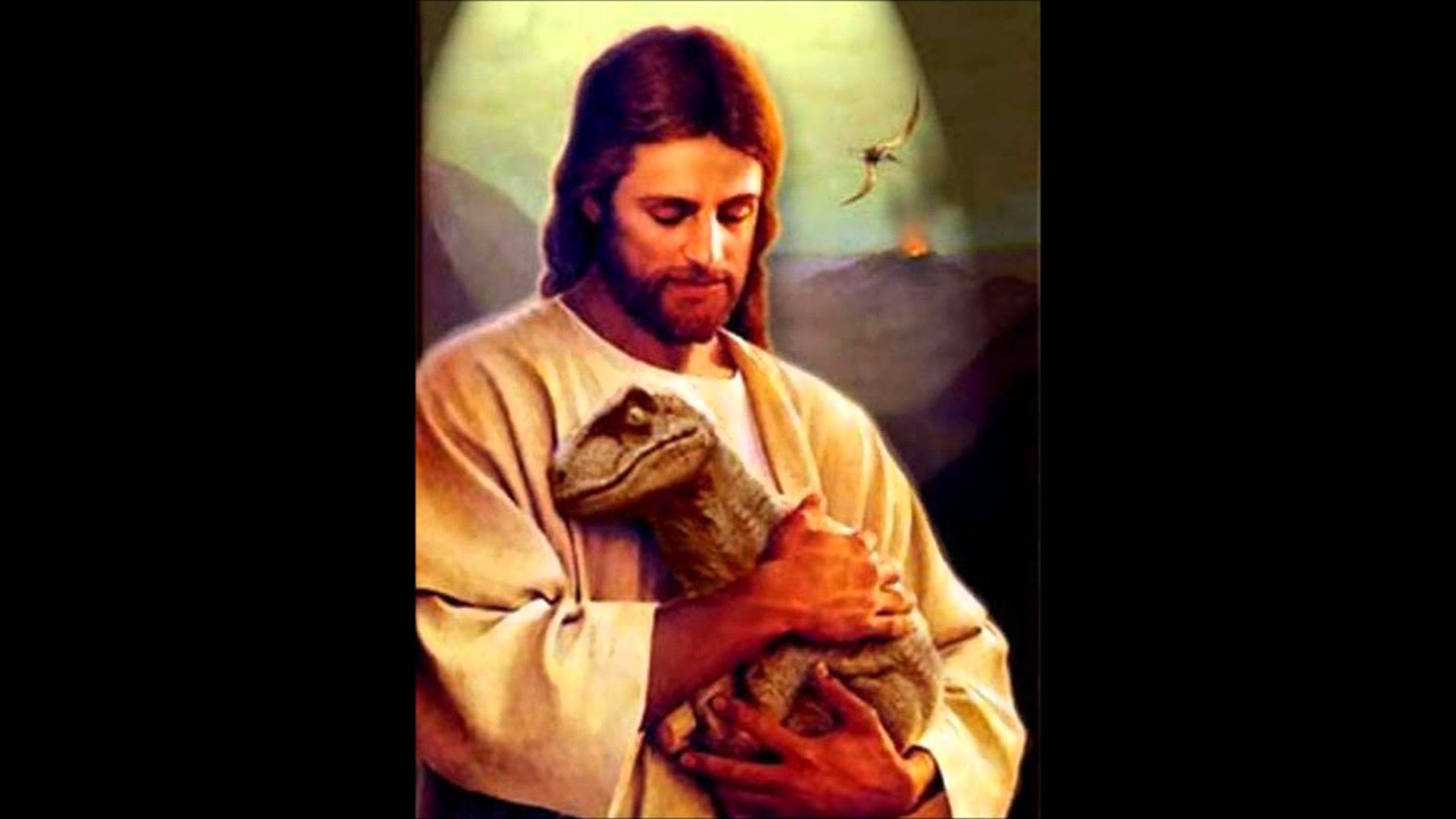

I love this picture of white Jesus clutching a baby dinosaur to his bosom. Apart from the fact that it reminds me of a young mother snuggling her sleeping baby (which makes me feel warm and fuzzy inside), I find this picture provocative and prophetic to the point of hilarity.

When I look at this white Jesus cuddling sweetly with a wee little reptile, I’m confronted with the question: Which is the more absurd part of this image — the cute baby dinosaur or the white Jesus?

White Jesus is prevalent year-round, but when the Christmas season rolls in, white Jesus becomes more immediately visible to the public eye. Nativity scenes with white baby Jesus grace the lawns of the faithful and their churches. Christmas cards, illustrated children’s books, movies, all manner of Nativity bling — it can be hard to find a holy family or shepherds or magi that aren’t white.

What’s up with white Jesus? Is there anything wrong with depictions of Jesus as white? Well, no. And yes. The answer depends on what ‘white’ means.

READ: Christianity is Not a White Western Religion

I once used the term ‘whiteness’ in a blog post in a pejorative way, and I remember a white reader expressing her frustration at this. When I said ‘white,’ she thought I was talking about pigmentation, the color of her skin, which of course she knew was a biological reality that she couldn’t change. Was I blaming her, myself, and other white people for our skin color?

What this reader heard as a criticism of her unalterably pale skin, I meant as a criticism of the arbitrary concept of ‘race’ that was invented by humans to dehumanize people of color. My intention wasn’t to bemoan a biological reality, but to draw attention to the venomous story of white supremacy that we’ve bought into.

This is where depictions of Jesus as white become an issue. The problem with white Jesus is not (and never has been) pigmentation, but the symbolic meaning that the inventors of ‘race’ poured into white skin, and the way these myths of white supremacy continue to permeate our culture and create real effects not only in our personal relationships, but in our legal, social, and economic structures.

‘Race’ is a social construct that has its origins in the European colonizers that wanted divine justification for their conquest of Africa and the Americas. The history and development of race was gradual and complex, but it boils down to a simple idea: you (1) divide humans into categories (races) based on the perceptions of white Europeans, (2) pass these off as innate, biological categories (i.e., God-made rather than human-made), and (3) argue that some races are lower than others. This then gives the ‘higher’ race divinely-sanctioned justification for its abuse of the ‘lower’ races and the right to take their land and enslave them.

‘White’ in this framework is a racialized category with legal and social ramifications. Although it shares overlap with physical characteristics (i.e., light skin), the two aren’t synonymous with one another. We see this, for example, in the way that the Irish immigrants who first came over to the U.S. were not initially considered ‘white’ even though they had white skin. The Irish, in fact, were demonized in many of the ways white American Protestants demonized Blacks, and experienced both legal and social discrimination and exploitation. Gradually, however, the Irish were incorporated as ‘white’ and acquired the legal, economic, and social benefits that whiteness affords.

What does this mean for white Jesus?

Because Jesus is understood symbolically by Christians as the quintessential human figure, there is nothing theoretically untoward about anyone picturing a Jesus who looks like them, even if it doesn’t align with the historical portrait of Jesus of Nazareth: a first-century Jewish man living in Roman-occupied Palestine (presumably of dark complexion).

All things being equal, there would be nothing wrong with light-skinned people envisioning a light-skinned Jesus, just as there is nothing wrong with African Americans imagining Jesus as an African American. If Jesus is the archetypical human figure, then all humans should be able to see their own singular lived human experience in the face of Jesus.

But all things are not equal. On this side of history, when the imaginary category of race has been (and still is) attached to physical characteristics to justify oppression, skin color is no longer a neutral category. White skin stopped being neutral the moment our white ancestors looked at their own white flesh, declared it ‘good,’ and in the same sentence declared dark skin ‘bad.’

We created white Jesus as an expression of our own singular humanity as white people, but because our lived human identity as defined by these racialized categories depended on the demonization and oppression of people of color, white Jesus became a symbol of colonization and white supremacy. The production of ‘race’ made our own worth as white people contingent on the debasement of others. Our identity became entangled with the vision of our own racial supremacy, which meant our Jesus did, too.

On this side of history, white people need to be saved from whiteness. Not saved from our white skin, but from the symbolic value that white supremacy vested in our skin. The only way we will be free, disentangled, is to have that identity deconstructed and rebuilt through the full liberation of people of color, whose lead we must follow as the guide back to our own humanity.

As a white woman, I need Black Jesus, Native American Jesus, Latinx Jesus. They are my salvation, my way back to the humanity that was lost to white supremacy.

READ: Theological Declaration on Christian Faith & White Supremacy

I grew up inundated with images of white Jesus, but I didn’t recognize this as an issue until I became an adult. Because my father was a Messianic Jew, I grew up very aware of the fact that Jesus was Jewish. But most of the Jewish men I knew personally were of European descent and had brown beards and eyes. While the occasional pictures of a blond-haired blue-eyed Jesus seemed bogus to me, my limited exposure to Jews who looked different from those in my immediate circle meant that I imagined Jesus was also white with brown hair and brown eyes. And this light-skinned image of Jesus was reinforced by all the pictures in the children’s Bibles and Bible movies I saw.

If you haven’t noticed, white Jesus is usually the only Jesus in town. If you dig, you can find other images of Jesus, but it’s hard. If that isn’t a symbol of white supremacy, I don’t know what is. The message is very clear. If Jesus the archetypal human must be white in order to be human, that means everyone else does, too.

When it comes to white baby Jesus in a Nativity scene, the idea of white Jesus seems even more ludicrous than white Jesus with a dinosaur, because white baby Jesus completely contradicts the spirit of the Christmas story.

At Christmas, Christians celebrate Jesus as the incarnation of God — divine being becoming flesh in a human person. As a symbol of incarnation, white baby Jesus sends a contradictory, but potent message: God’s presence is only manifest in white people. White baby Jesus says that “God with us” really means “God with white people.” Just as the “we” in the U.S. Constitution’s “we the people” restricts the definition of personhood to white, land-owning males, so the “us” in “God with us” restricts the locus of divine presence to white bodies.

I think we need to disarm white baby Jesus by laughing at him and calling his bluff. I mean, look, if this little guy is supposed to be deity stepping down into the vulnerability of human existence, is a white male infant the best we’ve got? Seriously?

No. If you really want to say, “God with us” — immensity of power and glory cloistered in the body of contingent human flesh, you look to those on the margins, those despised and disenfranchised by the dominant culture. Native American Jesus. Latinx Jesus. Black Jesus. Immigrant Jesus. Queer Jesus. Trans Jesus. The Jesuses whose glorious bodies reveal that the full breadth of humanity exists outside of participation in whiteness, and expose the lie that divine presence is inexorably confined to white bodies.

Dear white baby Jesus, I’m calling you out this Christmas. My own humanity is on the line. You may claim to stand for us all, but we know what you really are. Nothing but a white savior that demands humanity conform to the self-glorified image of your own white face.