48 years ago today, Father Dan Berrigan, his brother Philip, and seven others, who became known as the “Catonsville Nine, ” went into a Selective Service offices in Catonsville, Maryland, and burned several hundred draft records in a direct action against the Vietnam War. They were arrested, tried, and found guilty of destroying government property. After sentencing, Fr. Dan, who died on April 30th at age 94, asked the judge if the Lord’s Prayer could be recited. All in the courtroom, including the judge and prosecuting attorneys, rose and joined in the prayer.

Writing from his prison cell, Fr. Dan summed up the action the action in an apology. (Ever the scholar, he was no doubt thinking of the Greek, in which apologia is a public defense, not a confession of wrong doing.)

Pardon us, friends, for the fracture of good order,

for burning paper instead of babies.

I did not get to travel to NYC for Fr. Dan’s funeral a couple of weeks ago. Instead, I remembered him at home by reading through the file of letters we exchanged over the past fifteen years, since the horrors of 9/11 and our country’s response to it brought us together. The clarity and genuine grief with which he explained the Catonsville action was not exceptional. It’s who Dan was.

I met Fr. Dan while studying philosophy at Eastern College in Philadelphia. I was reading Alasdair McIntyre at the time, considering the plight of Western Civilization. Three airplanes were hijacked as I sat in a philosophy class one crisp, clear morning. We heard news of a crash in New York City, than stepped outside our classroom to watch the second plane fly into the World Trade Center. Almost immediately, the Muslim world became our enemy, and our President asked us to shop as we prayed for the troops he was deploying in a “war on terror.” McIntyre was right: the barbarians were not waiting at the gate. They had been among us–leading us even–and for some time. We had met the enemy and the enemy was us.

Dan always said it was his brother Philip who opened his eyes to the inherent violence of the American Way after his sojourn among black folks in Louisiana. Their church and their family had formed them in faith: when you see something wrong, you have to do something about it. But Philip was always the natural activist, Dan the poet. He came to Philadelphia that fall and counseled a small group of us recently awakened Christian activists. Turning the conventional proverb on its head, he called us to pay attention. “Don’t just do something; stand there.”

The great Southern writer Flannery O’Conner said that, to do her work, the writer must cultivate a capacity to stare longer than others do. Dan was a writer at heart. He knew how to stare and see deep down things. But he was also a preacher by vocation. Staring at the ugly realities of our common life that we are practiced in ignoring, Dan was a “keeper of the Word.” Scripture study mattered. He wrote once with an apology for his slow response; he’d been occupied with his regular pattern of gathering to read Scripture. Such was his work in the world, and he knew it.

In public, Dan is remembered for his arrests. He knew the inner tension that was created by the image of civil authorities cuffing a priest in his collar, walking him to a jail cell for preaching with his body where God’s Word is not welcome. Still, I don’t think he ever enjoyed it. He bore the mantel as Jeremiah had before him, a weeping prophet. He had a pastor’s heart.

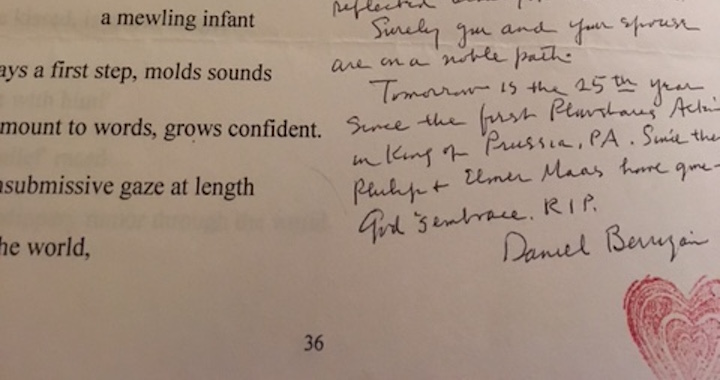

This is the Fr. Dan I got to know as a correspondent and recipient of spiritual direction via the US Mail. He did not shy from the truth, updating me on his health ailments or reprimanding me for ways that I was obviously thinking primarily of myself. Still, his tone was gentle, his reproach always accompanied by a smile you could almost see, a heart stamped on the page itself. It was this depth of compassion–this fully developed humanity–which added gravitas to the clarity with which Dan saw and named the world. It was, in the end, love which enabled him to to so ably sum up the way of Jesus:

If you’re going to follow Jesus, well, he got killed. That’s just part of the job description: making trouble for peace.