Should the poor have a right to a college education in the United States?

“Many people in our country no longer believe that college is a privilege to attend, but students believe it is their right and somebody else ought to pay for it, and not themselves.”

I recently heard these words spoken by a retired college administrator who still sits on important education policy boards.

I find his sentiment troubling, especially in light of a recent spate of studies that find poor and minority students are falling further behind in the race to gain a college diploma.

What would those holding it’s-not-a-right-but-a-privilege view say to these young people? Should only those with wealth attend our more expensive schools? Is the answer a two-track system in which bright students who mistakenly think they have a right to higher education be routed into underfunded two-year community colleges, leaving our private colleges and more selective public universities to the relative few deserving students who can afford to pay for it for themselves?

If some students are undeserving of a college education, and everyone should “pay it for themselves, ” who then is left in the category of deserving of the “privilege” of a college education? On this premise, should we establish a kind of a cut-off point for all admissions–say the 80th percentile of all test takers on the SAT test for a given year? And, of course, those top 20 percent would also need to have the resources to pay for the degree all by themselves.

Related: The Damaging Effects of Shame-based Sex Education: Lessons from Elizabeth Smart

Of course, there happen to be some really-smart-students who happen to also be really-not-rich.

Awilda Rodriguez, citing a study by ProPublica that looks at these trends over the last fifteen years, reports that there is a small increase in the number of students from disadvantaged families entering college. The bad news is that the data show they are attending colleges of quality levels below what their academic achievements and standardized test scores would qualify them to attend.

Rodriguez contours several reasons for this troubling trend:

- though students from disadvantaged families are attending college in greater numbers, they are enrolling in schools below their academic qualification levels, such as feeder two-year public schools or lower-tiered state and regional four-year universities.

- contrary to popular perception, between 1996 and 2012 fewer and smaller grants were given to students from the lowest income families each year; grant monies were instead redirected toward those with more resources.

- the chances of any student completing a degree through those lower-tier schools are significantly lower than at more selective institutions.

- the better schools are not actively recruiting underprivileged students and have, at best, budgeted for modest increases in the number of low-income students.

- even elite schools which trumpeted low or free tuition to highly qualified low-income students a number of years ago have quietly scaled back or dropped those financial-aid programs, the University of Virginian being but one recent example. Reason given? Too expensive.

- many of these more prestigious schools are also back-peddling on calendar adjustments and reinstating early-decision admission schedules, which force the hand of deciding students in the fall previous to the year students will attend a university. Many low-income students can’t commit that early since they need to know what financial-aid offers they will receive at the university and the others they will be applying to.

A study by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce found that high-scoring (top half ) SAT/ACT students enroll in college at similar rates regardless of race (white, black, or Hispanic), and that those high-scoring minority students who attended one of the nation’s 468 top schools were about twice as likely to graduate with the degree than those who attended the open-access schools and also had a greater chance of going on to graduate studies.

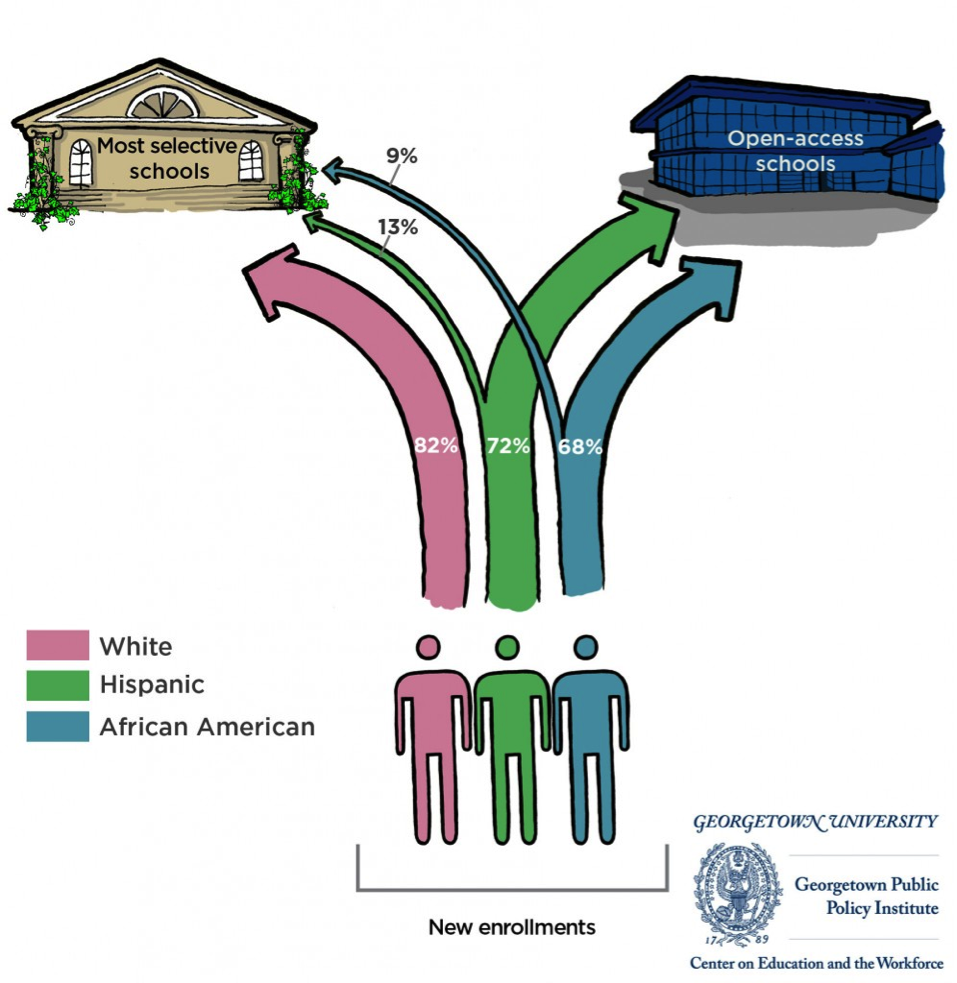

The catch, however, is that white students accounted for most of the enrollment growth at the nation’s top colleges while African Americans and Hispanics account for most of the increase in open-access two- and four-year colleges. That means there are now more white students proportionally at these selective universities than in decades past, and fewer black and Latino and Latina students represented in these more illustrious institutions of higher learning.

A 2012 College Board report confirms these findings and labels the phenomenon of students attending colleges and universities less selective than what their academic credentials would allow them to attend as “undermatching.” The report concludes that undermatching is “pervasive, especially among low-income students, minorities, and first-generation college goers.”

One example: roughly two in three graduating high-school seniors in the Chicago Public Schools in 2005 “undermatched.” The long-term difference in attending a more selective school is pronounced: a higher graduation rate, more success in the labor market, higher wages, less unemployment time, better health insurance, better retirement packages, greater health, and more job satisfaction.

The cumulative result is that few equally highly qualified poor students end up at the more selective schools with their richer peers. The bulk of these smart-but-poor students instead end up attending open-access institutions where their chances of academic success–and of even getting that diploma–are greatly diminished. The Georgetown report captures this dynamic graphically here:

The data suggests we have fashioned a new separate-but-equal higher education system in which the disadvantaged are tracked through two-year and open-access public institutions, while the advantaged are ushered into selective institutions and distinguished careers that continue to provide these privileged persons with perpetual advantages–or “blessings, ” as I hear so many white middle- and upper-income evangelical Christians blithely and euphemistically frame their privileged social and economic positions.

The same College Board report notes that only 28 percent of students attending two-year colleges go on to actually graduate with a degree or even a certificate–a rate about half that of students attending four-year institutions. Of course, this non-blessing is followed by a lifetime of lower wages and lower social status and wealth. Workers with professional degrees—three fourths of whom are white—earn $2.1 million more in wages in their lifetimes than those who dropped out of college, the Georgetown study round.

Also by Kevin: Why I’ve Stopped Saying ‘We are a Nation of Immigrants’

The view that a bachelor’s degree is a privilege-and-not-a-right I cited at the beginning of this piece wouldn’t matter so much if it weren’t emblematic of a larger elitist view present in some circles of higher education movers and shakers. Ironically, the same speaker also made this claim:

“We’ve already entered a time frame when much of the nation’s private wealth is being passed to a new generation–from a nation of people who saw themselves as givers to a younger generation who seem more inclined to be keepers and spenders.”

The speaker seemed to be lamenting the drop in donations to institutions of higher learning as the older generation of generous givers passes on. The question arises: Should individual students pay their own way but when it comes to colleges and universities, “somebody else should pay for it”?

What if those holding this exclusivist view would instead see making a bachelor’s degree an affordable right to all students who put in the study and work needed to complete it? What if we were to see the startling statistic–that 80 percent of Americans possess just 7% of the wealth while the richest 20% hold 93% of the wealth–and conceive of making a college degree financially feasible for all motivated students as an investment in the single greatest resource this country possesses by transferring some of that wealth?

What if he were moved by the fact that the state of New York spends on average as much incarcerating an inmate as it would take to pay four years of full tuition at Harvard University for that inmate?

Then the puzzle of what to do with the anomaly of the smart-but-poor student might be obviated.