In a misguided move for clarity, President Trump, along with the Health and Human Services Department, is suggesting that sex be defined as an immutable, biological fact, determined at birth as either male or female. According to a recent New York Times article, the proposed definition is aimed at erasing the civil rights protections of transgender people under federal civil rights laws — such as Title IX — that explicitly ban discrimination on the basis of sex but not necessarily gender identity.

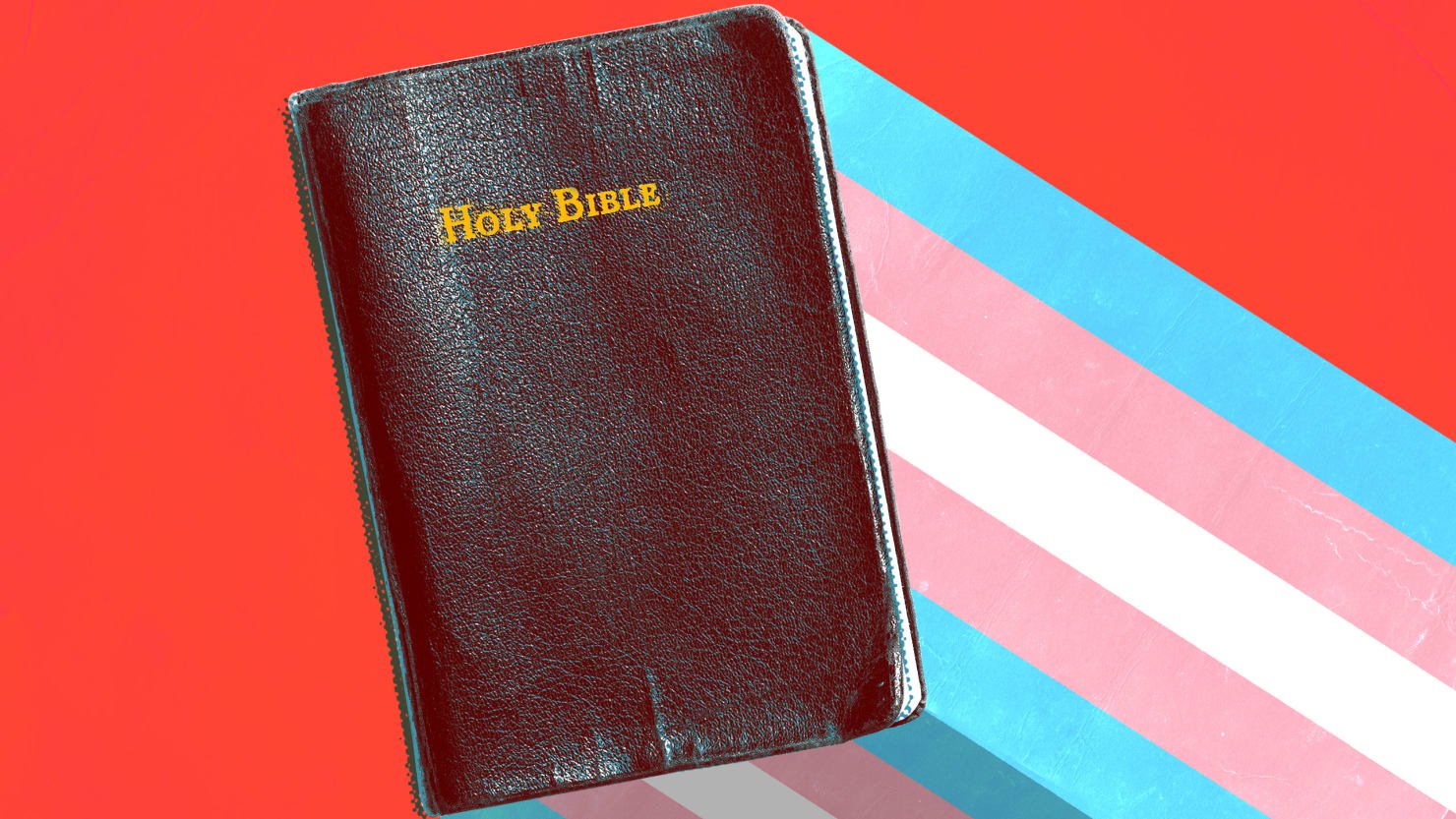

As a Christian, I find this narrow definition of human sexuality both laughable and lamentable — not just because biology does not support a neat, binary model of sex and gender but because, in my opinion, neither does the Bible.

I have two higher education degrees in gender studies — one in conjunction with a Bachelor’s in Anthropology and one in tandem with a Master’s in Theology — and still I find myself using words like sex and gender interchangeably. So let’s have a quick course of study on their differences:

Sex: A determination of your biological and genetic characteristics as male and/or female. Sex is a “determination” because some individuals’ mixture of chromosomes, genitals, and hormones at birth do not fall neatly into either category and doctors, parents, and sometimes even judges often work to mask these abnormalities in order to fit the two-sex model.

Gender: A determination of your symbolic or social characteristics as male and/or female. Gender is a “determination” because it doesn’t always correlate with the reality of your biological sex but how the performance of your behaviors are read by your culture.

So, when we read in Genesis 1:27 that “God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him, male and female he created them,” I believe we’re reading a theological account of sex differences.

And if we take that knowledge that we’re made in the image of God to be synonymous with that knowledge that we’re made male and female, then that suggests to me that our sex differences somehow are both representative of God and transcended by God.

Sex — and our accompanying but not always corresponding gender identities —thus matter inasmuch as they teach us about differentiated and embodied relationships, first and foremost to God, but also to one another.

Of course, there are all sorts of ways that Jews and Christians have tried to make sense of our theological beginnings. One viewpoint argues that the first ‘adam (the Hebrew word translated in the King James Version as “man”) was an androgynous figure only later split into two sexes. Another viewpoint posits that the “male and female” creation account in Genesis 1 was what God intended to do, but that the “male or female” creation story personified by Adam and Eve in Genesis 2 was what actually happened.

The most compelling reading for me, though, is one I learned from Duke Divinity Professor Dr. Anathea Portier-Young, in which male and female in Genesis 1:27, can be understood as points on a continuum rather than two discrete categories.

This reading relies on a literary device called merism, examples of which are found throughout the Old and New Testament when two seemingly opposites are used to describe the whole.

We still use merism in our everyday language. For example, to say you searched high and low is to say you searched everywhere: shin height, chest height, and tippy-toe height included. When Genesis begins by saying God created the heavens and the earth, it also means everything within them like night and day (and dawn and dusk), like earth and sea (and beachfront and riverbanks), like birds and fish (and the bewildering platypus), like male and female.

Here, male and female can be thought of as describing two sides of the same coin with layers upon layers of malleable metal in between.

Of course, some argue that while there may be such astronomical realities as pre-dawn and pre-dusk, sex differences are not so nuanced. I disagree.

Today, intersexed individuals, who quite literally embody both sexes, make up an estimated 1.7 percent of our population, according to Dr. Anne Fausto-Sterling, author of Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality.

Further, social philosopher Michael Gurian’s work has shown that bridge brains, that is brains which show nearly equal attributes of both the male and female brain, make up an estimated 1 in 5 human brains.

In scripture, Jesus even highlights the biological reality of eunuchs — men castrated at birth either through violence or by choice — a reality that would have gotten them called “half-men.”

I refuse to believe these people are any less a reflection of the image of God. By their very existence, they weaken the claim that there are only and ever two sexes assigned at birth and nothing in between.

And if there are not only and ever two sexes in nature and scripture, then it follows for me that there are not only and ever two ways to faithfully express our gender here and now.

Some of us are male and express ourselves primarily through what’s been defined as masculine behavior.

Some of us are female and express ourselves primarily through what’s been defined as feminine behavior.

Some of us, like me, believe that although I am sexed female, I carry both stereotypical masculine and feminine gender attributes within me. (I once heard this described on the Amazon show Transparent as being “low femme.”)

Some of us self-describe as omnigender in which even a continuum idea of male and female, masculine and feminine, feels confining.

Then there are the 1.4 million folks who are transgender, whose gender does not correlate with their assigned sex at birth. They are in need of protection under federal laws like Title IX, not just because they are human but because they are especially vulnerable to prejudice, discrimination, and violence.

The point is not for all of us to aspire to some perfectly androgynous middle ground. The point is to tap into the full image of God that is available to us now and to live into this life with a larger sense of possibility — and resiliency.

In his book Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life, Richard Rohr says that dualistic thinking might get us in the right ballpark, but non-dualistic wisdom opens wide the field of possibilities. There’s nothing inherently wrong with dualistic thinking. It’s how we’re wired to learn in the first half our life.

What is wrong is ignoring the evidence when life grows outside the lines, as the Trump administration has stubbornly done with its suggestion that there are two, and only two, immutable boxes for biological sex. We should always be suspect when clarity (also known as purity) is used to control human wholeness.

Whatever you think about the authority of scripture or the reliability of science, the irrefutable reality is that together we make up more than one sex and gender, and together is how we best image the love of God and the body of Christ.

One of my favorite examples of merism comes in Paul’s letter to the Romans (8:39) when he writes, “No power in the sky above or in the earth below indeed, nothing in all creation, will ever be able to separate us from the love of God that is revealed in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Amen, so be it.