Featured Photo Credit: Kris J Eden

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is Part II in a two-part series introducing the Doctrine of Discovery and Mark Charles’ effort to start a conversation about it among North American Christians. You can read Part I here.

In 1763, King George issued a proclamation known as the Proclamation of 1763. In this proclamation he drew a line down the Appalachian Mountains and essentially told the colonists they no longer had the right of discovery of the Indian lands west of Appalachia. That right was now reserved solely for the crown.

This is one of the places where the histories of Canada and the United States split. The colonies located in what today is known as the United States were angered by this proclamation. They wanted to keep the right of “discovery” for themselves, and so a few years later they wrote a letter of protest. In this letter they stated:

He [King George] has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.”

They went on in this same letter to address several other issues they had with the King, concluding with the following:

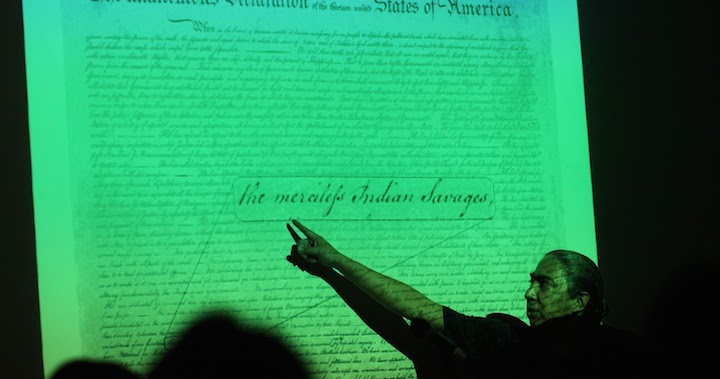

“He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages…

They signed this letter on July 4, 1776.

Yes, the Declaration of Independence, which so eloquently states “All men are created equal, ” 30 lines later goes on to dehumanize natives as “merciless Indian Savages.” The document that in many ways founded the United States of America hinges on a very narrow definition of who is actually human.

The colonies located in what is now known as Canada accepted the Proclamation of 1763 and did not revolt against the crown. However, this did not mean the empty Indian lands to the west could not be “discovered.” It merely meant that right belonged to Great Britain. Aboriginal people were still dehumanized, and our lands were still taken—it’s just that the injustices were done in the name of the Crown instead of the colonists themselves.

In the founding documents of the United States of America and in the implicit racial bias of Canada, Native peoples are defined as less than human and therefore are excluded from the broader group of “all.”

But we don’t talk about that.

In the United States, the issue and rights of “discovery” were crystalized with the following Supreme Court Case ruling:

As they [European colonizing nations] were all in pursuit of nearly the same object, it was necessary, in order to avoid conflicting settlements, and consequent war with each other, to establish a principle, which all should acknowledge as the law by which the right of acquisition, which they all asserted, should be regulated as between themselves. This principle was, that discovery gave title to the government by whose subjects, or by whose authority, it was made, against all other European governments, which title might be consummated by possession.”

US Supreme Court, Johnson Vs. M’Intosh (1823)

In 1823, the United States Supreme Court presided over a case brought by two men of European descent regarding a single piece of land. One bought the land from a Native tribe and the other bought it from the Government. They wanted to know who legally owned it. In reviewing the case the Supreme Court stated that according to the Doctrine of Discovery, Indians tribes only have the right of occupancy to land, while Europeans have the right of Discovery, and therefore true title to the land. This case helped establish a legal precedent for land titles based on the dehumanizing understandings of the Doctrine of Discovery. Lest this seem like ancient history, it should be noted that this legal precedent, and the Doctrine of Discovery, was referenced by the United States Supreme Court as recently as 2005 (City of Sherrill Vs. Oneida Indian Nation of New York).

The histories of Native peoples in both the US and Canada are largely similar; discovery, expansion, bloody wars, stolen lands, broken treaties, residential/boarding schools, cultural genocide, dehumanization and marginalization. If there is a difference, it seems to only be that the Canadian government, churches and people are more passive-aggressive in their injustices while Americans are more explicit.

The United States sees itself as a City on a Hill with a self-proclaimed “Manifest Destiny, ” while Canadians tend justify their expansion through economic benefits and solidifying their national identity. The United States developed the idea of Indian Boarding Schools with the explicit stated intention of “killing the Indian to save the man.” Canada took that concept and built on it, making residential schools a formidable part of its national aboriginal policies.

Both nations have a history of expansion, economic opportunity and aboriginal/Indian policies based on the implicit racial bias defined by the Doctrine of Discovery which dehumanizes people of color.

But we don’t talk about that.

Starting a (Difficult) Conversation

I have traveled extensively throughout the US and visited parts of Canada lecturing and speaking about the Doctrine of Discovery. I would estimate that less than 2% of the populations from either nation have a knowledgeable understanding of the Doctrine of Discovery.

On June 11, 2008 from the floor of the House of Commons, in a speech that was broadcast throughout the country, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally apologized to the First Nations people of Canada for that country’s history of residential schools.

This apology was part of a settlement to a lawsuit brought against the government and the churches by residential school survivors. The settlement also set aside approximately $60 million for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. And while this apology and the resulting Truth and Reconciliation Commission dealt with the injustice of residential schools, it did not touch on the Doctrine of Discovery.

In the 1950’s and 60’s the United States had one of the deepest conversations on race in its history, the Civil Rights Movement. However, the Doctrine of Discovery was not a part of that dialogue. In fact, one of the moral authorities used in that movement was the Declaration of Independence. So instead of discussing the fact that the US was systemically racist down to its very foundations, including the Declaration of Independence, the public rhetoric affirmed America’s foundations and merely encouraged people to live up to those ideals.

The governments, churches and people of the United States of America and Canada do not talk about the Doctrine of Discovery. We have removed it from our common memory. Instead we talk about our common ideals, or about our stated values for equality and justice.

Or we remain silent.

Throughout its history the United States has worked hard to define racial identity to the benefit of the dominant white race. For people of African descent there was the one drop rule. This rule simply states that if you had one drop of African blood you were black and could be enslaved. Slaves were the free labor source of this growing nation, so it makes perfect sense that the founders would want that pool to be as large as possible. For natives there is the blood quantum rule. This rule states that you can be full, half, quarter, eighth, sixteenth, and eventually your native/tribal identity can be bred out of existence. The United States teaches the myth that this continent was “discovered” by Europeans. Discovery assumes there was nobody here. It was the land Europeans desired. So the less natives there are, the easier it is to perpetuate the myth.

Because of these understandings, the U.S. has been forced to acknowledge, face and in some ways deal with its history of slavery—though unevenly and inadequately. But it has also allowed the nation to ignore, bury and deny its unjust history against natives.

On December 19, 2009, President Obama signed House Resolution 3326, the 2010 Department of Defense Appropriation Act. On page 45 of this 67-page bill, section 8113 is titled “Apology to Native People of the United States.” What follows is a 7 bullet-point apology that mentions no specific tribe, no specific treaty, and no specific injustice. It basically says “you had some nice land, our citizens didn’t take it very politely, let’s just call it OUR land and steward it together.” And it ends with a disclaimer stating that nothing in this apology is legally binding.

To date, this apology has not been announced, publicized, or read by the White House or Congress.

Creating a common memory

Georges Erasmus, an Aboriginal leader from Canada, once said “Where common memory is lacking, where people do not share in the same past, there can be no real community. Where community is to be formed, common memory must be created.”

This quote gets to the heart of both nations’ problem with race. Our citizens do not share a common memory. People of white European ancestry remember a history of discovery, open lands, manifest destiny, endless opportunity and exceptionalism. While communities of color, primarily those with African and indigenous roots, have the lived experience of stolen lands, broken treaties, slavery, boarding schools, segregation, cultural genocide, internment camps and mass incarceration.

But how do we do it? How do we create common memory where so much government, institutional, church and individual effort has been invested in consciously forgetting?

I recently attended the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada. And I applaud the progress that was made there, just like I applaud and honor the work of Civil Rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. But I also know the conversation must go deeper. The United States must find a way to talk about the fact that its very foundations are systemically racist and assume the dehumanization of people of color. And in Canada, the dialogue must extend beyond the limited legal parameter of residential schools. Neither nation can create a common memory until the Doctrine of Discovery is fully on the table.

And that won’t happen until we intentionally decide to talk about it.

9 months ago I moved with my family to Washington DC for the express purpose of networking and exploring ways to initiate a national dialogue regarding the Doctrine of Discovery. I have been greatly encouraged by the vast number of people and communities open to teaching this history and confronting these injustices. Two months ago I recorded a short video that articulated the vision for a national Truth and Conciliation Commission in 2021 (#TCC2021) and the steps we are taking to get there. I welcome you to watch it.