“Everyone’s a socialist in a pandemic,” writes Farhad Manjoo of the New York Times. Similarly, American political theorist Jodi Dean writes:

“[T]he truth of capitalism presents itself in all its naked horror in a crisis. Everyone hates the hoarders and profiteers. We appreciate purchase limits, laws against price gouging. We all recognize that healthcare is too important to be left to the market. As the cruelty of the market appears without its ideological sheen, more and more people realize the necessity—for the good of all—of free medical care, of paid medical leave, of a social safety net. Everyone’s a socialist now (whether they have recognized it or not).”

Dean and Majoo are among many pointing out that COVID-19 is highlighting America’s systemic flaws and showing how the myth of rugged individualism fails to provide what human societies need to flourish.

I was born and raised in conservative evangelicalism in the United States. Although I no longer identify as a Christian, I spent 25 years intimately engaged as a person of faith, scooping up three degrees in theology and biblical studies in the process. There was a tacit agreement in the Christian community of my formative years, which was deeply aligned with Republicanism, that capitalism was the most effective economic system for humans.

This ideology was (in part) grounded in a theological conviction commonly known as the doctrine of original sin: humans are born sinful (and by extension selfish). While we viewed selfishness as a negative trait, we also believed humans were incapable of substantial transformation until they were perfected by God in heaven. Since humans were bound to be stubbornly rivalrous in pursuit of personal gain, what could be better economically than a system that appeared to capitalize on this inherent selfishness?

Even before I left Christianity, seeing the problems of capitalism raised a big question for me: Are humans naturally selfish?

As I studied the Bible more deeply and was exposed to a variety of Christian traditions, I gradually learned other ways for Christians to understand their relationship to God, other humans, and the cosmos. The Hebrew Bible in particular gave me another impression: humans are complicated. Morality is a purely relational concept. Humans aren’t imbued with a natural inclination toward “sin” in the abstract.

Rather, humans exist in relationship to what they perceive as “others” (e.g., other humans, non-human animals, technological creations), even though nothing is truly separate or independent of its ecosystem. These relationships hold the potential for both cooperative generativity and relational transgression. Consent isn’t just for sex: when we violate the boundaries of the “other,” this creates rifts in need of repair (which often entails reparations).

In the Hebrew Bible, this is obviously framed theistically. The divine is presented as keenly aware of systemic injustice and communal failure to cultivate equitable social structures. But neither is this failure inevitable: humans are invited to partner with a divine creator to imagine (and actualize) a just world that operates on principles of abundance instead of scarcity. A world in which we view “others” not as threats, but as neighbors to share and collaborate with.

As the child of a Jewish parent, I was very invested in understanding Jesus as a first-century Jew. The more I studied Jesus in this context, the more vividly he appeared to be rooted in the tradition of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible. Like many of his prophetic forebears, Jesus seemed to believe the God of his ancestors had given their community a concrete way to partner with the divine to heal the world: by living out the ethics of Torah. Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5-7) underscored the idea that Torah wasn’t intended as an inflexible moral code, but to help the community realize the sort of peace and justice their God wanted to see in the world. And, rather than embracing a kind of fatalistic mentality, Jesus seemed to believe that people were actually capable of doing this.

These stories compelled me as a Christian, but as I moved away from religion, I wanted answers that didn’t rely on theism (or non-theism). My goal was to find the origins of inequality and imagine what an egalitarian society might look like. I discovered (spoiler!) that human growth is not the result of competition but cooperation. As you’ll see, some evolutionary anthropologists argue that egalitarian cooperation was what “made us human.”

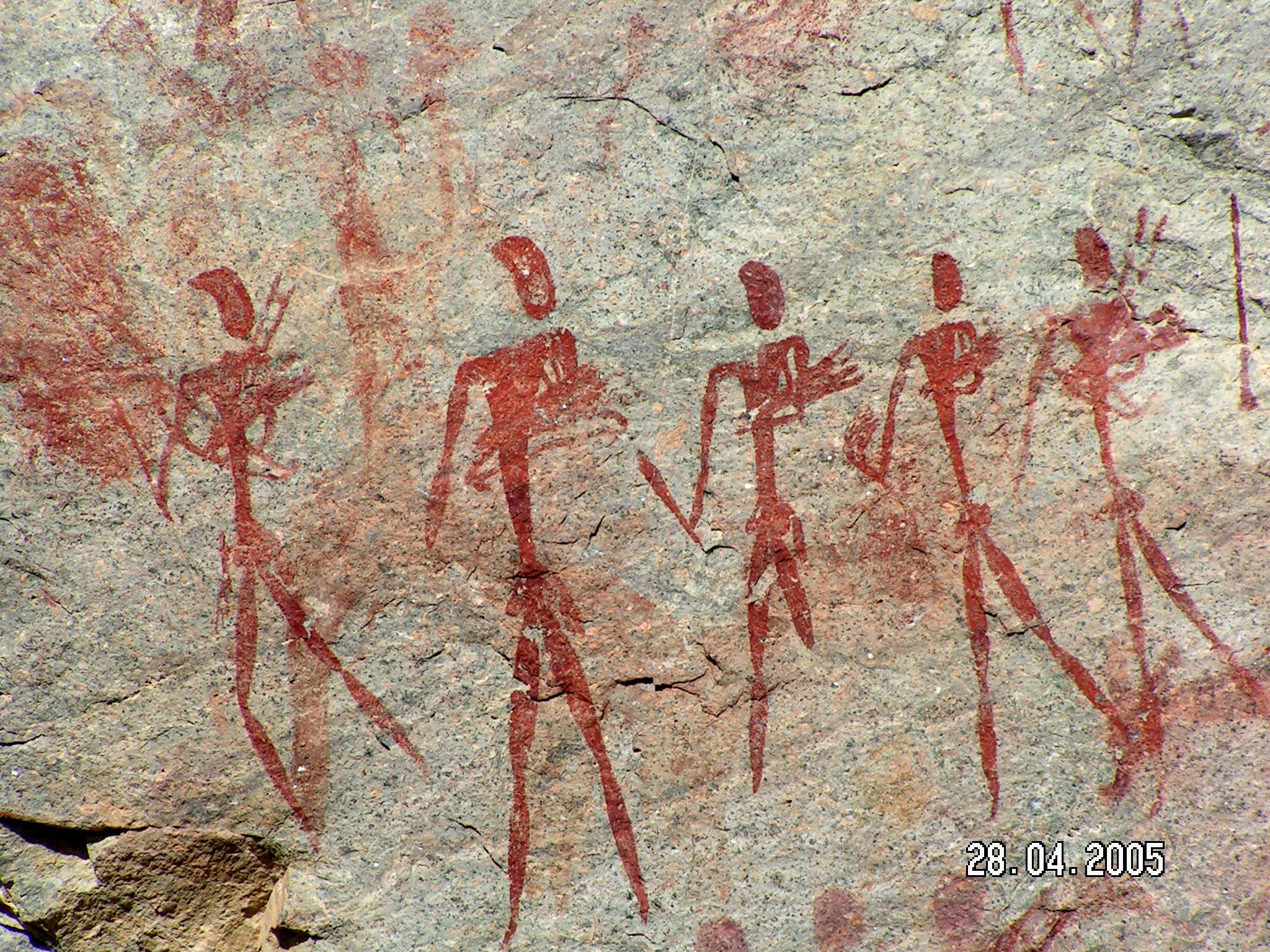

Earth’s oldest known civilization emerged around 75,000 BCE, but anthropologists tend to date the development of unequal social structures around 15,000-10,000 BCE. The prevailing theory is that although homo sapiens as a species emerged around 200,000 years ago, they were nomadic hunter-gatherers that moved around in small groups that were relatively (though not absolutely) egalitarian.

These groups weren’t naïve about the potential for inequality to develop; as anthropologist James Woodburn argues, egalitarianism isn’t neutral or passive, but is asserted. Hunter-gatherers practiced what’s been termed “reverse dominance hierarchy” to prevent potential “upstarts” from getting too much power. Nonetheless, so-called immediate return societies (they don’t have to wait for their food) tend to be more conducive to egalitarianism than delayed return agricultural societies, which necessitate longer-term investment in a specific area to procure food.

With the development of agriculture around 10,000 BCE, humans gradually exchanged a roaming, hand-to-mouth lifestyle for a life of land cultivation and animal domestication. The basic gist is that this First Agricultural Revolution paved the way for social hierarchy on a massive scale. Things like agricultural surplus, population growth, and property ownership contributed to the development of inequality (in part) by encouraging territorialism regarding land and the accumulation of goods.

Anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow have recently challenged aspects of this narrative, arguing that archaeological evidence from the last 40,000 years shows that humans experimented with various types of governance. Looking at the Upper Paleolithic (c. 50,000-10,000 BCE), they contend that population growth and the establishment of cities does not de facto lead to hierarchy; rather, some of the first cities were largely egalitarian. Graeber and Wengrow assert that Upper Paleolithic humans played with seasonal governance, employing both hierarchical and egalitarian structures at different times of the year.

However, as anthropologist Camilla Power points out, Graeber and Wengrow don’t really speak to the “origins” of human society since their study is limited to the Upper Paleolithic. Social anthropology from an evolutionary lens provides insight into human societies long before this period. Graeber and Wengrow also don’t discuss Africa at all, even though homo sapiens (modern humans) have been in Africa twice as long as they’ve been on any other continent.

Power suggests not only that homo sapiens emerged primarily as egalitarian hunter-gatherers, but that gender equality is what “made us human.” In a fascinating lecture, Power argues that the rapid and unprecedented increase in human brain size that took place between 800,000 and 200,000 BCE was driven by cooperative behavior among males and females.

These conversations deserve more attention, but here are some key takeaways. First, Wengrow and Graeber note that complexity and hierarchy are often used synonymously. If we have evidence, however, for societies engaging in cyclical shifting between egalitarian and hierarchical governance, this suggests that hierarchy is not necessarily a more “complex” form of governance.

Second, if humans were playing around with different forms of governance long before widespread agrarianism and land ownership, it suggests that although the First Agricultural Revolution undeniably hastened the development of large-scale hierarchy and systems of inequality, these are not necessary features of delayed return societies. In other words, we don’t have to adopt hunter-gatherer lifestyles, for equality to become a reality.

Although we don’t need proof that humans were “originally” egalitarian to make a case that equality is possible, Power’s account of how human brain size increased through cooperation is plausible. At a minimum, it coheres with current evolutionary thought that suggests cooperation is integral to evolution. Biologist Lynn Margulis writes:

“The view of evolution as a chronic bloody competition among individuals and species, a popular distortion of Darwin’s notion of ‘survival of the fittest,’ dissolves before a new view of continual cooperation, strong interaction, and mutual dependence among life forms. Life did not take over the globe by combat, but by networking.”

It’s valid to fear that humans won’t come together for the common good, especially when we see the damaging, individualistic “America first” mentality modeled by our own president. But although COVID-19 is highlighting some of the worst human behavior, we’re also seeing communities showing up for each other even though the United States’ governance system is designed to make the rich richer at the expense of others. If we can manage to still be human and show up for each other despite this terrible system, imagine what we could do with better infrastructure and social safety nets.

I’m not saying the future is inevitably bright. But at the very least, let’s not buy the lie that we are incapable of rallying as a globe to stop the spread of COVID-19 and rebuild together. Humans are not doomed to failure and we can do better. History says we can.