Praying with the Street Church of Radical Forgiveness

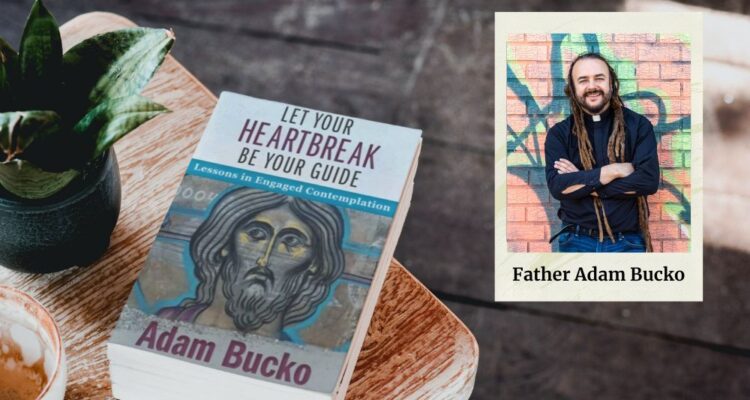

by Adam Bucko

from his book Let Your Heartbreak Be Your Guide

Each year when we commemorate the anniversary of 9/11, I remember well all the images of that day. The horror and devastation are still very present with me, even now. I also remember that in the days following the tragedy, here in New York, glimmers of hope and resilience began to emerge. People spontaneously began gathering in public places, like Union Square in Manhattan, to commence impromptu public grieving ceremonies. There were Buddhist monks praying for compassion. There was Rev. Billy, an actor fashioning himself as a priest of the church of radical forgiveness, offering absolutions to anyone who was willing to confess their sins. There were young Muslim activists correcting inaccurate portrayals of Islam by our media and proclaiming Islam as a religion of peace. All of a sudden there seemed to be enough money to care for the poor. If you looked unwell, strangers would come up to you on the NYC subway and make sure that you were all right.

Grief softened our hearts, and pain made us aware of other people’s suffering. There was a certain holiness in the air during those days. We were seeing with new eyes and hearing with new ears.

But then, about two weeks after the tragedy, we were told that everything needed to go back to normal. Memorials were cleared out of public spaces. Public prayers were discouraged. To be normal, we were told, was to go shopping because that was good for our country. To be normal, we were told, was to cease congregating in public places. We were told to go back to normal and that we did. It’s just that normal was not really normal to begin with.

Around that time, a friend invited me to a Bible study, without providing too many details. I simply knew that it was located on the Upper West Side at a community house of Jesuit priests. The class was led by an elderly man named Dan. He seemed like a very kind and gentle man. His voice was soft, and his insight into the text quite profound. It felt like he lived the text we were studying. It was only afterward that I discovered that this man “Dan” was the famous Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, who had spent his life protesting the values of American society that he felt contradicted the gospel of the nonviolent Jesus. His protests included hundreds of acts of civil disobedience, an illegal trip to Vietnam in the midst of the American invasion of Vietnam, and even time in hiding during which he topped the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

I met Dan a couple more times after that first encounter. He was invited to preach at a post 9/11 wedding of a friend at a Polish Catholic Church in Brooklyn. I’ll never forget the confused facial expression of the very traditional Polish priest who was officiating the wedding when he realized that Dan was preaching a sermon about the then-recent American invasion of Iraq. The Polish priest’s eyes were screaming, “This is a wedding! You should be preaching about love!” But, you see, in Dan’s mind he was preaching about love. Because for him love was not love unless it completely transformed us and changed how we live, what we say yes and no to, and how we let Christ live, love, work, and protest through us. Also, since in the Christian tradition marriage is supposed to be an earthly analogy for union with God, the kind of love that needs to be preached at a wedding is a love that is not small and fluffy but a love that’s got edges and is willing to suffer bruises in its commitment to embody what Christ stood for in the world. (Dan didn’t explain that in his sermon, and I never said any of that to the Polish priest, but perhaps I should have!)

In Matthew 18, we are presented with an illustration that takes place after a full day of ministry, following Jesus’s instructions to the disciples about being good shepherds. The disciples have been quarrelling about how many chances they should give to people who keep on missing the mark and making mistakes, even the same mistakes. How many times should we forgive those who harm us? Given that, in the first century, the typical rabbinic standard was to forgive up to three times, Peter might have thought his suggestion to forgive seven times was generous. Jesus’s response, however, was shocking. He said that we shouldn’t just forgive three or four or even seven times. We should forgive seventy-seven times, and there really should be no limit to our forgiveness.

Commenting on the importance of this limitless forgiveness, another great teacher, Henri Nouwen, said:

“To forgive another person from the heart is an act of liberation. We set that person free from the negative bonds that exist between us. We say, ‘I no longer hold your offense against you.” But there is more. We also free ourselves from the burden of being the “offended one.’ As long as we do not forgive those who have wounded us, we carry them with us or, worse, pull them as a heavy load. The great temptation is to cling in anger to our enemies and then define ourselves as being offended and wounded by them. Forgiveness, therefore, liberates not only the other but also us. It is the way to the freedom of the children of God.”

Forgiveness doesn’t have to mean forgetfulness. To forgive is to cancel the expectation of payment for the offense and to be free from any attempt to “get even.” To forgive is to choose not to carry the burden with us anymore and to be open to the freshness of a new start. Forgiveness opens up possibilities for healing, reconciliation, and mercy—but not just mercy, also justice, the kind of justice that seeks not to punish but to heal.

Speaking of the freedom that forgiveness offers, I am reminded of one of the thousands of stories of perpetrators and survivors of the Rwandan genocide who took refuge in the practice of forgiveness that Jesus proposed. Jean Claude was a young eleven-year-old in Rwanda when the genocide began there. Tragically, as he hid in the bushes, he watched as neighbors tortured, mutilated, and murdered his father, sister, aunts, and uncles. After the genocide, Jean Claude wondered how to move on and eventually made the choice to forgive those who had murdered his family. Years later, he started a nonprofit to help poor and orphaned children. Most of the children that his organization supported came from the families that committed the genocide. When asked about his choice to support orphaned children of those who committed all the atrocities he said, “If I could not have forgiven, I would have said that I can only help the genocide survivors. But then I would not be able to help this one child that I now love so much. He is a child of a man who participated in the killing of my father. After the genocide when his father was imprisoned for his crimes, I knew that this child needed help. I decided to adopt him. I knew what it felt like to lose a father and I didn’t want him to have the same experience that I did. So I took him in and now am raising him as my own son.”

This is what forgiveness in action looks like and this is how the gospel is lived in real life.

So now I return in my memory to the aftermath of 9/11, and I imagine what might have happened if the screams of pundits who occupied our media, many of whose voices are still present today, had been replaced by the voices of people like Jean Claude, willing to do the hard work of putting forgiveness in action. How would these intervening years have been different if restorative justice had been our guiding principle? Imagine if on September 12th, instead of rushing into the logic of retaliation and war, we had taken a pause to fast, and to pray, and to deeply listen to the grievances of those who had been hurt as a result of our policies and presence? Just imagine how different our lives and our politics would be today.

We can’t go back and fix all the mistakes of the past, but we can move forward by going inward, searching our hearts for those hard areas in need of the giving and receiving of forgiveness, praying “Abba . . . Father, forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

Excerpted from Let Your Heartbreak Be Your Guide by Adam Bucko. Published by Orbis Books. Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2022 by Adam Bucko.