Approaching racial segregation and injustice from the perspective of discipleship can move white Christians to a place we have rarely gone—to lived and sacrificial solidarity with our neighbors. There is nothing quick or simple about this. Our definition of discipleship implies the lifelong formation of communities of Christians: Following Jesus (into the kingdom of God) to become like Jesus (through habit shaping practices that orient our desires) in order to do what Jesus does. But for this discipleship to effectively confront the other discipleship of our racialized society, we need to be precise about the challenges that await us. Otherwise, the cultural tools to which white Christianity defaults will undermine our best efforts.

It’s important to realize that a discipleship approach to racial justice and reconciliation depends on a community of Christians. There’s nothing especially innovative about this; for generations, Christians have gathered for corporate worship and, by participating in shared liturgical practices such as singing and Holy Communion, have together had their desires aimed toward the kingdom of God. By its very nature the Christian life is communal; individuals find new life within the locally expressed body of Christ. It’s not that we lose our individuality when we become Christians, but that who we are as individuals finds fuller and truer expression within the community of saints.

As basic as the corporate nature of the faith is to Christianity, it can be a hard thing to remember in a society that holds individuality as one of its highest values. A number of years ago, as we were just starting our church, one of my mentors told me that the hardest part of planting a church would be simply learning to be the church. This made no sense to me at first—the hardest part of starting a church was just getting a few people to show up! But over time, his wisdom became clear. It’s one thing to gather a collection of individuals; it’s something else entirely for those individuals to see themselves as a community, as a people with a shared identity who, despite countless differences and disagreements, commit to remaining with one another.

So the discipleship practices that orient us toward the reconciled kingdom of God are corporate practices, which means that white Christians must begin thinking of ourselves not only as individuals but also as a group. And in my experience, this is tough! When I talk to white Christians about racial reconciliation or the importance of multicultural ministry, the response is typically enthusiastic. But if I begin talking about white people, white Christianity, or even racial whiteness, the response is tepid or sometimes combative. When mixed with our racialized society, the problem of individualism is that many white people refuse to see ourselves as white. We want to be thought of only as individuals.

As the cultural majority in this country, the problem for white people is that we don’t think of ourselves as a distinctive culture but as the neutral standard by which other cultures are categorized. As a white man, I can go through my life unaware of what it means to be white. My assumptions, histories, aspirations, and even my physical representation are portrayed in textbooks and media as the cultural norm.

READ: In the Era of Ahmaud, What Does Solidarity Have to Do With Jesus?

The ubiquity of white culture makes it a challenging dynamic for white people to claim. Then there is the disturbing way that white culture, when it is publicly claimed, is done so by avowed racists and ethnonationalists—hardly the sorts of movements most of us want to be associated with! Despite these real obstacles, for white Christianity to move beyond its segregation, we must recognize our whiteness. But for now we must acknowledge that we have been born into a world that sees us as racially white and assigns us certain unearned privileges because of it. When I begin a conversation with something like, “As a white man . . .” I am acknowledging the way our racialized society has categorized me and, more difficult to admit, the ways I’ve internalized this racial sorting.

This doesn’t mean that I should only be known by my white identity; my extended family, diverse neighborhood, and church community are all groups wherein I am shaped and known. But it does mean that, in order to resist the hyperindividualism that typically subverts white Christians’ attempts at racial justice, I must come to see that I am not culturally neutral but a member of a particular racial and cultural group.

Because of my commitment to racial justice, I sometimes receive emails from friends and family members with links to heartwarming stories about racial reconciliation. Sometimes these are videos about former avowed racists having been befriended by a person of color and changing their racist ideology. Others have been news stories about white police officers who go out of their way to care for a black or brown young person who needed a helping hand. These emails always make me smile; in the midst of so much racial injustice, any little reason for encouragement goes a long way. But they also point to another of white Christianity’s overused tools: relationalism. Because white Christians reduce systemic racial inequity to broken relationships influenced by personal prejudice, the most common approach to addressing racial injustice has to do with building or restoring personal relationships.

Relationships across cultural divides are essential to the biblical vision of reconciliation, but the way personal, individual relationships are elevated in white Christianity above systemic change and social justice is a huge barrier to that same biblical vision. We are right to grieve the segregation within the body of Christ.

As important as racial reconciliation is, our goal is not to make every white church racially diverse but to move these churches toward lived solidarity with the entire body of Christ. By acknowledging and confronting racial discipleship, our reimagined discipleship practices will begin forming communities to confess and confront the conditions that cause segregation and injustice.

This is why focusing on discipleship is not an easy way out for white Christians. Quite the opposite! While welcoming people of color into our congregations or ministries would scratch our relational itch, the underlying factors related to our segregation remain unaddressed. In contrast, by reorienting our desires and imaginations toward the reconciled kingdom of God—a formation involving the reshaping of longheld, often unconscious racial habits—we are doing the difficult work of facing our complicity with the injustices suffered by our family in Christ. We are also committing to the sacrificial journey of solidarity that, while certainly relational in character, will lead us to confront the material sources of our segregation. This is a risky journey, one that requires deeply formed love for our King and his kingdom.

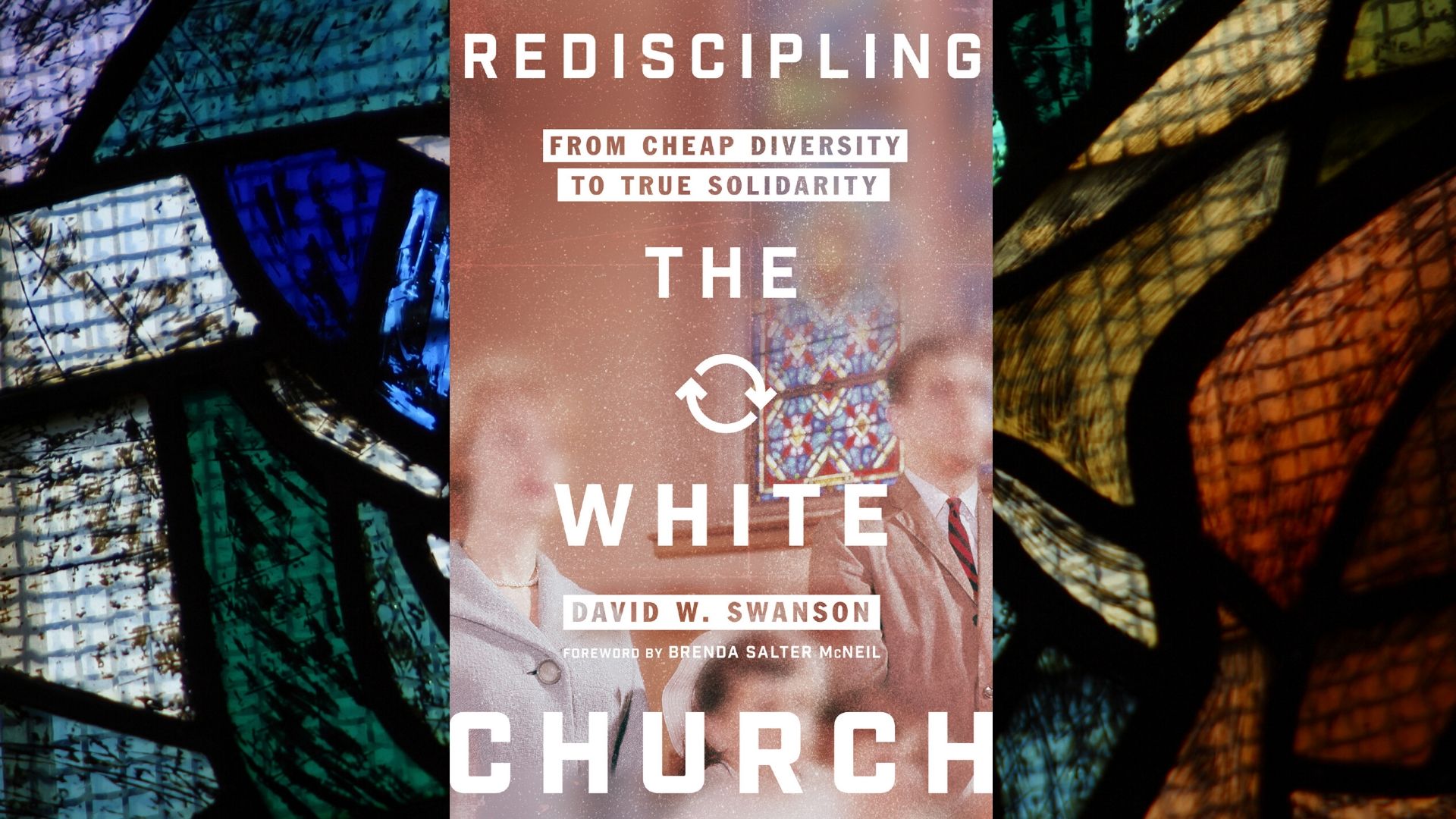

Adapted from Rediscipling the White Church by David W. Swanson. Copyright (c) 2020 by David Winston Swanson. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com