Content taken from Tears of Gold by Hannah Rose Thomas, ©2024. Used by permission of Plough Books.

Excerpt from the Foreword

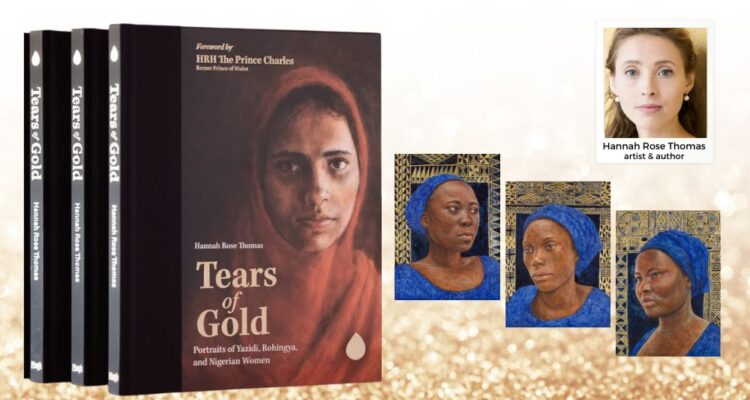

One of Hannah’s aims is to capture not only the courage and stoicism of the women who have suffered so much, but also the nobility, dignity, and extraordinary compassion that many of them manage to retain, despite their traumatic experiences. Her use of traditional painting techniques along with gold leaf (learned at my School of Traditional Arts), together with her spiritual outlook and intention, elevates the portraits to almost the status of icons–transforming the particular into the archetype and the individual mother into the Universal Mother, thereby speaking to every woman.

I very much hope that this beautiful book, Tears of Gold, will help enable the Yazidi, Rohingya, and Nigerian women’s voices to be heard, as well as to highlight the issue of the persecution of religious and ethnic minorities in general. All too often, their stories of suffering remain unseen and unheard–but Hannah Thomas is doing tremendous work in bringing their stories out into the open. May her powerful paintings spread the word and, God willing, have a positive impact in relieving the suffering of some of the most vulnerable and marginalised communities around the world.

– HRH The Prince Charles, former Prince of Wales (prior to his accession as HM King Charles III)

Portraits of Nigerian Women

Survivors of Boko Haram and Fulani Violence

Since the beginning of the Boko Haram insurgency in northeast Nigeria in 2009, millions have been forced from their homes. Boko Haram abducted thousands of women, holding them captive and subjecting them to sexual violence and forced marriage. After the kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in Chibok in April 2014, the hashtag #bringbackourgirls went viral, retweeted by celebrities and politicians from Kim Kardashian to Michelle Obama.

Since then, the security situation in northern Nigeria has been further exacerbated by escalating conflict between predominantly Muslim and nomadic Fulani herdsmen and Christian farmers. Fulani militants have used sexual violence to target women as a way to devastate communities. A report released by the UK government in 2020 describes the targeting of Christian communities in Nigeria as an “unfolding genocide.” (1)

In September 2018 I spent a week in northern Nigeria, leading an art project facilitated by Open Doors as part of a trauma healing programme with Christian women who were survivors of sexual violence either at the hands of Fulani militants or Boko Haram. As with my other projects, the aim was to create a safe space for the women to share their stories and begin to process their pain.

Like the Yazidi women in Iraqi Kurdistan, many opted to add glistening tears of gold to their self-portraits. For the finishing touch the women sewed vibrant local Nigerian fabric onto their paintings–with a lot of singing and laughter, which was beautiful to see! The women were so proud of the self-portraits they had created.

Charity had been kidnapped by Boko Haram and held captive for three years. When she returned with a baby, her husband beat her and refused to accept the child. On our last day together for the art project Charity said, “I am so happy. I have never held a pencil in my life before, and this is the first time I have been able to write my name and even to draw my face!” The art project was a drop in the ocean when I think of the trauma she has faced. Yet the simple act of drawing a self-portrait helped her affirm her identity and value, especially important considering the shame and stigma that victims of sexual violence face in her community.

Conflict leaves many wounds, but perhaps the hardest to overcome is this ongoing stigma that so many survivors have to contend with. This additional burden, following devastating assaults, is almost unbearable. The perceived association of survivors and their children born of wartime rape with the enemy entrenches the stigma and often leads to further abuse, (2) as does the absence of cultural narratives that allow women to look upon their survival as heroic or honorable. (3 )

Dr. Denis Mukwege, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, writes, “As individuals and societies, we need to show . . . compassion and kindness to all survivors. Sadly, instead, we do the opposite. We compound their pain by treating them with suspicion, or worse, treating them as pariahs. The shame and costs of an assault all too often fall on women, not their aggressors. They deserve sympathy, support, and protection.” (4)

Living through and surviving sexual violence can be an isolating experience. Art workshops can be a safe, nurturing, and nourishing space to break that isolation–“the idea of feeling surrounded by acceptance and protection, a space where it is possible to be oneself, devoid of threat, and to get on living life without fear.” (5) These projects can become a source of connection, an occasion for showing empathy, care, trust, and creativity–the conditions needed to reclaim human dignity. (6) By the end of the week in northern Nigeria, the women were all laughing, dancing, and singing together–a complete transformation from our first day.

One girl who took part in the art project, Florence, had been raped by Fulani militants when she was ten years old. On our last day together she said, “Here I have found peace of mind.” Initially Florence had kept her face covered and eyes averted; now she met my gaze with the most radiant smile.

Again, the purpose of the project was twofold: it was both therapeutic and also for advocacy–to empower the women’s voices to be heard through their self-portraits. The women’s self-portrait paintings have been shown alongside my portrait paintings in places including the UK Houses of Parliament, Lambeth Palace, and Westminster Abbey to shine a light on the issues of sexual violence and the persecution of religious minorities. In this way, the women are being a voice for other women who are also targeted on account of their religion and their gender. As one participant, Aisha, said: “I want the whole world to know that I have pain. I have gone through a lot, and many other women in my village are going through a lot, and that is what is happening here in my country. Women are going through a lot and they do not have anybody to speak out for them.”

Following my return to England from Nigeria, I poured my heart into painting portraits of the women. I used sacred imagery and early Renaissance tempera and Byzantine icon painting techniques. The headdresses are a vivid blue made from lapis lazuli, a precious pigment mined in Afghanistan, so expensive that it was traditionally reserved for paintings of the Virgin Mary. The patterns in gold leaf are inspired by indigo-dyed fabric from the region.

I hope the paintings have captured a glimpse of these women’s extraordinary courage, strength, resilience, and dignity–to show that they have not been defined by what they have suffered.

These portraits were unveiled in Lambeth Palace in November 2018, alongside the self-portraits painted by the women. The paintings have gone on to be displayed in places including Westminster Abbey; the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office; Government Communications Headquarters; and churches across the United Kingdom. Open Doors UK & Ireland ensured that each of the women received a copy of my portrait painting and her self-portrait.

Gambo

Gambo

I regained consciousness and found that I had no clothes on my body. I tried to stand up but couldn’t stand.

Gambo was gathering firewood in 2018 when a Fulani herdsman ran towards her brandishing a stick and demanded, “If you do not allow me to sleep with you I’m

going to kill you.” She later regained consciousness–naked, bleeding, and unable to walk.

Gambo’s body still has not fully recovered when I meet her in September 2018, and she is in the process of taking the perpetrator to court. Drawing her self-portrait, she explains her mixed feelings: “The first is a feeling of anger and bitterness and that is why I drew myself not smiling. The second feeling is a feeling of joy, knowing that God loves and still protects and takes care of me.”

Aisha

Aisha (28)

I had no peace in my heart.

I couldn’t eat, and I couldn’t sleep.

Whenever I was alone, I remembered how those two men raped me. It is a wound

that takes a gradual process to heal.

A group of Fulani men attacked Aisha’s village at night. They took her husband away when they saw he had a

Bible and brutally raped her in her own home. Amazingly, Aisha’s husband was not killed. When he returned, he

showed her the support many women in Aisha’s situation do not receive. He assured her, “I will never leave you, so

I’ll stand by you.”

“I want the whole world to know that I have pain,” Aisha says. “I have gone through a lot, and many other women in

my village are going through a lot.”

Esther

Esther

How people treat my daughter really makes my heart ache.

Esther and her family were hiding in the caves in the hills, in fear of Boko Haram. When she returned to the village for food one day, Boko Haram attacked and she was taken into the Sambisa Forest, where the Chibok girls were also held.

Esther was in captivity for three and a half years. She was sold as a slave and forced to become the fourth wife of a Boko Haram leader. When this man was killed, Esther and the other wives escaped, trekking for three days without food or water and with no shoes on their feet. Esther was seven months pregnant.

After time being held in a military camp, Esther returned to her village.

When she arrived home, Esther’s family tried to make her abort the baby, but she refused.

After Rebecca was born, the family rejected her, calling her “Boko.”

FOOTNOTES: Portraits of Nigerian Women

1 “Nigeria: Unfolding Genocide?: An Inquiry by the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group for International Freedom of Religion or Belief” (June 2020).

2 United Nations Security Council, Women and Peace and Security, III.C.41.

3 David J. Morris, The Evil Hours: A Biography of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015), 70.

4 Denis Mukwege, The Power of Women: A Doctor’s Fight to End Violence against Women

around the World (London: Short Books, 2021), 327.

5 Lederach and Lederach, When Blood and Bones Cry Out, 64.

6 Eva Feder Kittay, “A Theory of Justice as Fair Terms of Social Life Given Our Inevitable

Dependency and Our Inextricable Interdependency,” in Care Ethics and Political

Theory, ed. Daniel Engster and Maurice Hamington (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2015), 67.