In the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic, people around the world face stay-at-home orders. A new and infectious disease can easily overwhelm our healthcare systems in any one place if we do not take extreme measures to slow its spread and “flatten the curve,” as we’ve learned to say. Thousands of doctors, nurses, public health officials, and janitors are rushing to the the frontlines of this dangerous struggle. But their message to the rest of us is clear: the best thing we can do is stay home.

At some point in the coming months, this will be the reality for almost everyone on earth. But while we are at home, how can we keep from being overcome by boredom, depression, or anxiety? What can we do during quarantine to become the sort of people who can build up a better world?

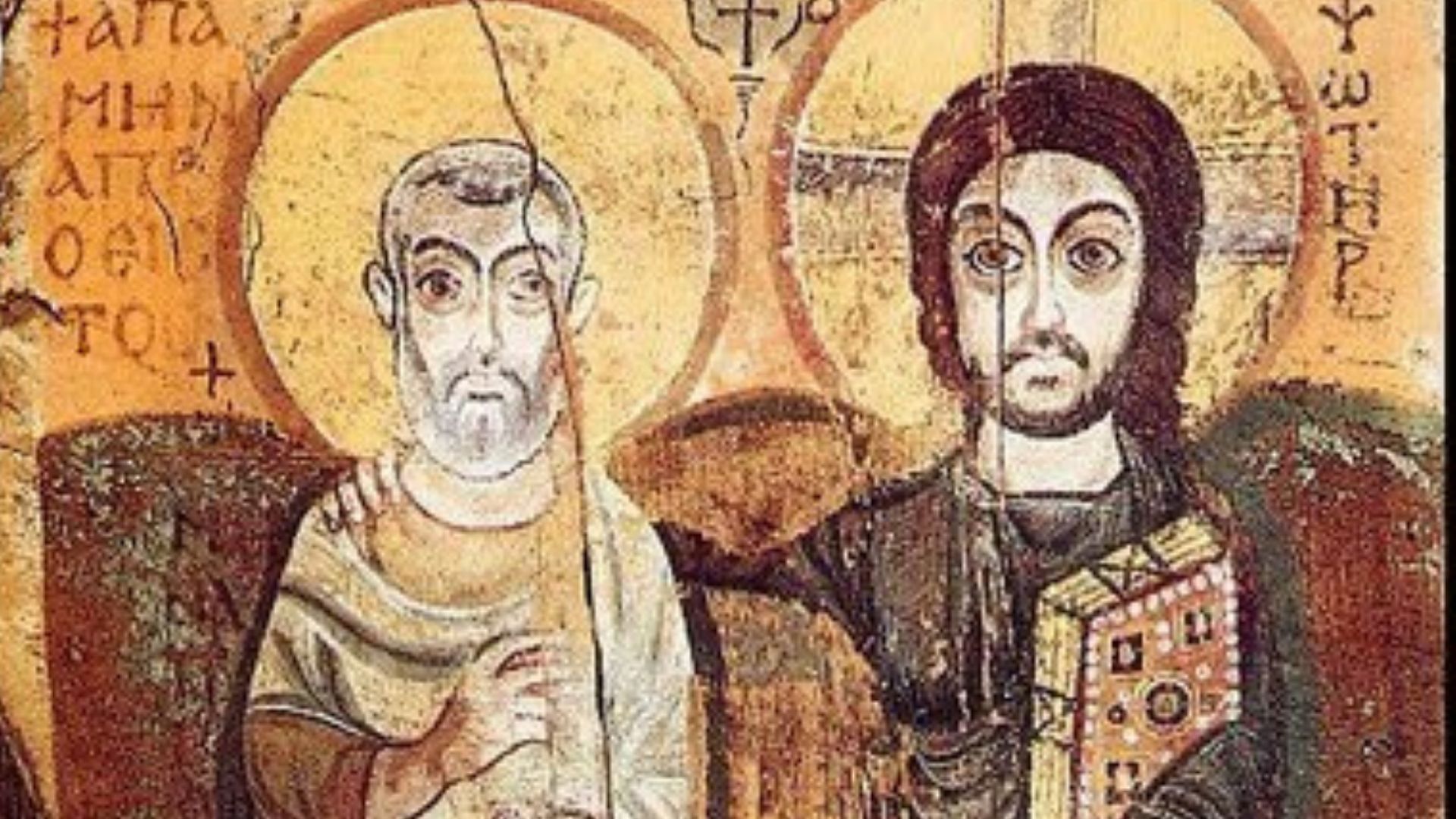

While there may not be any time in history when most people on earth faced this particular challenge, there is a long tradition of people who have embraced long-term isolation for the sake of their own growth in service to the world. As our household learns to live under a stay-at-home order, I’ve been thinking about the wisdom of the desert mothers and fathers from 3rd and 4th century Egypt and Syria.

“Go into your cell and your cell will teach you everything,” Abba Anthony, the father of desert monasticism taught. The cell became a teacher for thousands of women and men who fled the cities of Roman society. “The desert became a city,” one observer wrote, struck by the sudden mass appeal of the ascetic life. Each monastic sat in a cell alone, stripped of the normal conveniences and pattern of their former lives. They did not have a set of books to read, a 12-step program, or a series of lectures to listen to online. But they were conscious of the need to re-train their whole selves for a new way of life. Isolation itself, they learned, can teach us who we really are and who we want to become.

The cell taught them, among other things, the importance of rhythm to an integrated life in isolation. Of course, nature is filled with rhythm, as day turns to night and winter turns to spring. In normal life, societies have a rhythm too. Meetings are scheduled, planes take off, school bells ring, and meals are served. We set alarms to teach our bodies the rhythms of our world. But in isolation, we lose our schedule. We sleep in, forget to eat lunch, miss Zoom meetings or forget what day it is.

READ: Prayer and Action: Like Breathing In and Out

The ammas and abbas of the 4th century taught that our bodies and our spirits need a rhythm of going back and forth between work and contemplation. The Benedictines would eventually make this insight their motto: ora et labora—prayer and work. But for the early monks in isolation, it was a basic realization that we grow in the way of love as we make time each day for both soul work and practical necessities. Human transformation doesn’t come through a retreat from ordinary life. It comes as we reimagine how we spend our days.

In the quiet of prayer—what we usually call contemplation—the desert monastics found that the strife they had hated in society was in fact inside of them. Amidst the ebb and flow of this prayer and work, they noticed the thoughts that troubled their spirits and stirred inside each of them. “Logismoi”—bad thoughts—couldn’t be ignored or drowned out by conversation or entertainment. Isolation drew out their twisted desires and impure motives. They learned not to blame others or to run away, but to face these thoughts. They could not make them disappear, but they did get to decide how to respond to them. Recognizing that became its own kind of freedom.

No doubt, the boredom, depression, self-importance and twisted desires those ancient monastics learned to name and wrestle will be there for each of us as we face isolation in the months ahead. In the story of Abba Anthony, he had an experience of being assaulted by these thoughts and feeling like a physical being had jumped on top of him with its hands around his neck. Anthony called on the name of Jesus and experienced relief in that moment, but the monastics passed on his experience as a way of remembering that facing what we find in the cell teaches us to turn from our own strength and ability to God. Yes, we get to choose how we respond to bad thoughts. But they are often stronger than we are. And so we must learn to root our life in something stronger than we are.

Because they recognized human dependence, the desert monastics also advocated a practice they called the “manifestation of thoughts.” It wasn’t enough to recognize the inner struggle and turn to God for strength. The ammas and abbas also advocated a regular practice of sharing with someone else the experiences they had in isolation. In our modern era, telephones and the Internet make it possible to maintain quarantine without losing human connection. Monastic wisdom suggests that we need to regularly share our dreams and struggles with someone else. And we need to trust their feedback. It’s easy to get lost in ourselves during times of isolation. If a trusted ear tells you that you need help, listen to them.

We are not the first humans to face extended periods of isolation. Some of the desert monastics stayed in their cells for decades. But the tradition eventually embraced a new vision of life together that centered on love of God and love of neighbor as the true purpose of human life. That vision led to a monastic movement that shaped the modern world, giving us, among other things, hospitals that serve the medical needs of all people in the midst of a pandemic. If the desert mothers and fathers had not done the work required of them in isolation, we would have never had the communities that created the hospitals and universities that are working today to help humans survive COVID-19. By doing the work before each of us who are called to isolation in this moment, we can become the sort of people we need to be in order to imagine a more just world after this pandemic.