Dear Readers,

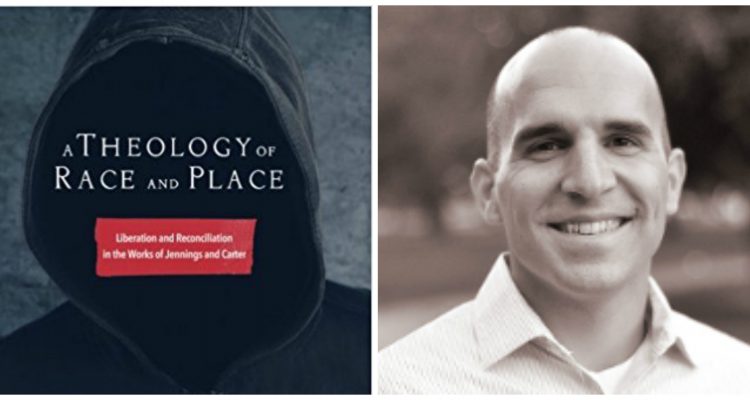

I want to recommend a book which has some unique insights about race relations. A Theology of Race and Place was born out of Andrew T. Draper’s experiences in the beautiful yet messy work of reconciliation in a local urban church context.

While pastoring a multiethnic church, Draper found that the common ways many evangelicals thought about racial reconciliation were inadequate for the task of articulating what is at stake theologically when people are joined together across ethnic lines. This is especially the case when being joined across the black-white divide in America, animated as it is by a tortured history of subjugation, injustice, and oppression.

Many books have tried to tackle this subject in various ways, but no work has been as compelling as the recent theological work of Willie James Jennings and J. Kameron Carter, sometimes called “the New Black Theology.” Draper works with their theological race theory to propose a vision for a church that is marked not by assimilation or paternalism but by relationships of mutual vulnerability.

As the first book-length treatment of the theologies of Jennings and Carter, Draper’s work makes a much-needed contribution to discourses surrounding race, reconciliation, church, and place. In an era of racial profiling and exclusion of the “other,” Draper presents a critical yet hopeful vision for the joining work of the gospel.

Sincerely,

Tony Campolo

Editor’s Note: In his book, Draper applies theological race theory to the shooting of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager who was killed by George Zimmerman on February 26, 2012. While Zimmerman was arrested and charged with second-degree murder and manslaughter, he was acquitted of all charges in July 2013. This excerpt is used with permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers.

…After several days, I noticed that, of the hundreds of people who had responded, every person who had challenged me was white. People of various ethnicities had shared a sense of concern or outrage at the manner in which the trial was progressing. When I publicly noted this observation, I was chastised with the “post-racial” assumption that we now live in a “colorblind” society in which the ethnicity of a view’s proponents means nothing. What matters is whether or not a person’s observations are “right.” Invoked to bolster this view was Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream that his children would be judged not by “the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” It seemed to me that this utilization of King appropriated his words out of context and insinuated that while ethnicity meant nothing, the innate character of the nonwhite other was readily discernible.

I was told that to talk about race as playing a substantial role in ethical discourse serves to stoke the flames of racial division and strife, turning back all the “progress” we have made as a society. How was I to interpret these critiques from “good” people about a society that has presumably “gotten over” ethnic division? Were it not for my experience of the racial calculus that operates reflexively within contemporary theological and ecclesial formation, I might have more seriously questioned my assumptions about the death of a black youth and the acquittal of his killer.

While I had long recognized problematic aspects of my own formation in regard to the assumed universality of what were highly culturally constructed theological, aesthetic, and ethical frameworks, it is through the works of Willie James Jennings and J. Kameron Carter that I began to link things I had observed, but not been able to connect or explain in a coherent fashion. What had been troublesome in the way “reconciliation” was imagined within the ecclesiological frameworks I had received was explicated in their texts in a cogent manner that purposed to expose the inception of the racial vision and its subsequent masquerade as universality. Jennings’ and Carter’s related genealogical accounts present whiteness as a sociopolitical order that must be maintained and invested in so as to be given life. As such, whiteness as a comprehensive way of life can function as a challenge to the Way of Life embodied in the One who is the Way. It will become clear throughout this study that what I am referencing as problematic is not the particularity of European experience, but the particularity-as-universality that is whiteness and which competes with the reign of Christ as it invites all flesh into its sociopolitical order.

… While it was a foregone conclusion for my brothers and sisters in the black community that in some way every aspect of this tragedy had been about race, and while I took comfort in the strength I borrowed from them, I was not sure how I would be received the next morning. Zimmerman was acquitted on a Saturday night and Sunday morning I would be standing to preach before the joined black and white community that makes up the congregation which I pastor. I needed to put into words the sadness and outrage which we felt, while clinging to the hope that mutuality is possible within the body of Jesus of Nazareth. What happened was not what I expected. The building in which we worshiped was full and our members, black and white, were there and ready to worship. The African American members of the body experientially led our congregation, including those of a lighter hue, into an affirmation of God’s goodness in the face of injustice. Even after having lived and ministered in my community for years and after having availed myself of many autobiographical, theological, and sociological resources related to the struggle for black liberation upon the soil of the New World, I was existentially unprepared for the familiarity of the black worshipper with exalting the name of the Lord while walking through the valley of despair. While I was able to speak to the deep sense of betrayal we as a community were experiencing, the maintenance of an affirmation of God’s goodness did not rely primarily upon me. We had together formed a bond strong enough that we were able to be vulnerable with each other in the midst of our pain instead of alienating each other because of the perpetration of evil. I will never forget the heroic posture of my black brothers and sisters that morning as those of us who had not been on the receiving end of racial profiling were invited into the shared experience of lament and celebration.